| |

|

Holy

Trinity, Blythburgh

|

|

Perhaps some counties have

a church which sums them up. If there has to be

one for Suffolk, it must be the church of the

Most Holy Trinity, Blythburgh. Here is the late

medieval Suffolk imagination writ large, as large

as it gets, and not overwritten by the Anglican

triumphalism of the 19th century. Blythburgh

church is often compared with its near neighbour,

St Edmund at Southwold, but this isn't a fair

comparison - Southwold church is much grander,

and full of urban confidence. Probably a better

comparison is with St Margaret, Lowestoft, for

there, too, the Reformation intervened before the

tower could be rebuilt. The two churches have a

lot in common, but Blythburgh has the saving

grace. It is so fascinating, so stunningly

beautiful, by virtue of a factor that is rare in

Anglican parish churches: sheer neglect.

Holy Trinity, Blythburgh, is the church that

Suffolk people know and love best, and because of

this it has generated some extraordinary legends.

The first is that Blythburgh, now a tiny village

bisected by the fearsome A12 between London and

the east coast ports, was once a thriving

medieval town. This idea is used to explain the

size of the church; in reality, it is almost

certainly not the case. Blythburgh has always

been small. But it did have an important medieval

priory, and thus its church attracted enough

wealthy piety on the eve of the Reformation to

bankroll a spectacular rebuilding. |

It is to Lavenham, Long Melford, Mildenhall, Southwold

and here that we come to see the late 15th century

Suffolk aesthetic in perfection. But for my money, Holy

Trinity, Blythburgh, is the most significant medieval art

object in the county, ranking alongside Salle in Norfolk.

Look up at the clerestory; it seems impossible, there is

so much glass, so little stone; and yet it rides the

building with an air of permanence. Beneath, there is a

coyness about the aisles that I prefer to the mathematics

of Lavenham. Here, it could not have been done otherwise;

it distils human architectural experience. If St Peter

and St Paul at Lavenham is man talking to God, Holy

Trinity at Blythburgh is God talking to man.

At the east end, a curious series of initials in

Lombardic script stretch across the outer chancel wall.

You can see an image of this at the top. It reads

A-N-JS-B-S-T-M-S-A-H-K-R. This probably stands for Ad

Nomina JesuS, Beati Sanctae Trinitas, Maria Sanctorem

Anne Honorem Katherine Reconstructus ('In the name of the

blessed Jesus, the Holy Trinity, and in honour of Holy

Mary, Anne and Katherine, this was rebuilt'). A fanciful

theory is that they are the initials of the wives of the

donors. However, note the symbol of the Trinity in the T

stone, and I think this is a clue to the whole piece.

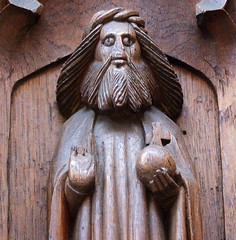

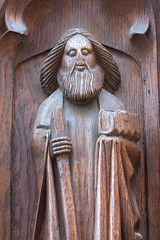

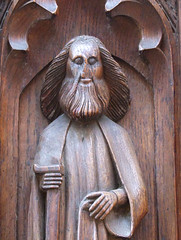

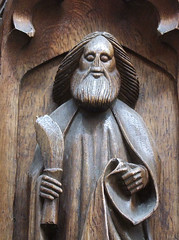

Figures stand on pedestals atop the south side and east

end. The most easterly is unusual, a crowned old man

sitting on a throne directly on the gable end. This is a

medieval image of God the Father, a rare survival. Moving

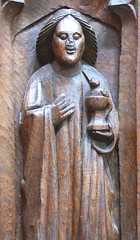

westwards from here we find the Blessed Virgin in

prayerful pose, Christ as the Saviour of the World

holding an orb in one hand and blessing with the other,

and then a collared bear with a ragged staff, a seated

woodwose, another bear, this time with a collar and bell,

and last of all a fox with a goose in its mouth, his jaws

grasping the neck:

The porch is part of the late 15th century rebuilding,

but it was considerably restored in the early 20th

century. Interestingly, the angels crowning the

battlements look medieval - but they weren't there in

1900, so must have come from somewhere else. Pretty much

all the porch's features of interest date from this time.

These include the small medieval font pressed into

service as a holy water stoup, and image niche above the

doors. This has been filled in more recent years by an

image if the Holy Trinity; God the Father holds the Son

suspended while a dove representing the Holy Spirit

alights; you can see medieval versions of this at

Framlingham and Little Glemham. Of all medieval imagery,

this was the most frowned upon by puritans. An image of

God the Father was thought the most suspicious of all

idolatries. Indeed, as late as the 1870s, when the

Reverend White edited the first popular edition of the

Diary of William Dowsing, he actually congratulated

Dowsing on destroying images of the Holy Trinity in the

course of his 1644 progress through the counties of

Suffolk and Cambridgeshire.

William Dowsing visited on the morning on April 9th,

1644. It was a Tuesday, and he had spent most of the week

in the area. The previous day he'd been at Southwold and

Walberswick to the east, but preceded his visit here with

one to Blyford, which lies to the west, so he was

probably staying overnight at the family home in

Laxfield. He found twenty images in stained glass to take

to task (a surprisingly small number, given the size of

the place) and two hundred more that were inaccessible

that morning (probably in the great east window). Three

brass inscriptions incurred his wrath (but again, this is

curious; there were many more) and he also ordered down

the cross on the porch and the cross on the tower. Most

significantly of all, he decided the angels in the roof

should go.

Lots of Suffolk churches have angels in their roofs. None

are like Blythburgh's. You step inside, and there they

are, exactly as you've seen them in books and in

photographs. They are awesome, breathtaking. There are

twelve of them. Perhaps there were once twenty. How would

you get them down if ordered to do so? The roof is so

high, and the stencilling of IHS symbols would also have

to go.

Perhaps this was already indistinct by the time Dowsing

visited. Perhaps Tuesday, 9th of April 1644 was a dull

day.

Several of the angels are peppered with lead shot. Here

is another of those Suffolk legends; that Dowsing and the

churchwardens fired muskets at the angels to try and

bring them down. But when the angels were restored in the

1970s, the lead shot removed was found to be 18th

century; contemporary with them there is a note in the

churchwardens accounts that men were paid for shooting

jackdaws living inside the building, so that probably

explains where the shot came from. Here are some details

of that wonderful roof:

The otherwise splendid church guide

also repeats the error that the Holy Trinity symbol in

the porch filled a gap that had been 'empty since 1644'.

But there was certainly no image in it when Dowsing

arrived here, or anywhere else in Suffolk; statues were

completely outlawed by injunctions in the early years of

the reign of Edward VI, almost a hundred years before the

morning of Dowsing's visit.

Another feature used as evidence of puritan destruction

is the ring fixed into the most westerly pillar of the

north arcade. Cromwell's men stabled their horses here,

apparently. Well, it almost certainly is a ring for tying

horses to, and the broken bricks at the cleared west end

also suggest this; but there is no reason to think that

Cromwell and the puritans were responsible. For a full

century before Cromwell, and for nearly two hundred years

afterwards, a church as big as this would have had a

multitude of uses. Holy Trinity was built for the rituals

of the Catholic church; once these were no longer

allowed, a village like Blythburgh, which can never have

had more than 500 people, would have seen it as an asset

in other ways. It was only with the 19th century

sacramental revival brought about by the Oxford Movement

that we started getting all holy again about our parish

churches. Perhaps it was used as an overnight stables for

passing travellers on the main road; not an un-Christian

use for it to be put to, I think.

In August 1577, a great storm brought down the steeple,

which fell into the church and damaged the font. This was

at the height of Elizabethan superstition, and the devil

was blamed; his hoof marks can still be seen on the

church door. Supposedly, a black dog ran through the

church, killing two parishioners; he was seen the same

day at St Mary, Bungay. Black Shuck is the East Anglian

devil dog, the feared hound of the marshes; and Holy

Trinity is the self-styled Cathedral of the Marshes, so

it is appropriate that he appeared here. You can see

where the font has been broken. You can also see that

this was one of the rare, beautiful seven sacrament

fonts, similar in style to the one at Westhall; but, like

those at neighbouring Wenhaston and Southwold, it has

been completely stripped of imagery. Almost certainly,

this was in the 1540s, but there is a story that the font

at Wenhaston was chiselled clean as part of the 19th

century restoration. More importantly in any case, the

storm, or the dog, or the devil, damaged the roof; it

would not be properly repaired for more than 400 years.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, accounts note

that Holy Trinity is not impregnable to the weather. By

the 19th century, parishioners attended divine service

with umbrellas. By the 1880s, it was a positively

dangerous building to be in, and the Bishop of Norwich

ordered it closed.

Why had Holy Trinity not been restored? Simply, this is a

big church, with a tiny village. There was no rich

patron, and in any case the parishioners had a passion

for Methodism. Probably, repairs had been mooted, but not

a wholesale restoration as we have seen at Lavenham, Long

Melford and Southwold. By the 1880s, attention in England

had turned to the preservation of medieval detail; in

short, restorations were not as ignorant as they had been

a quarter of a century earlier. Suggestions that Holy

Trinity should be restored in the manner of the other

three were blocked by the Society for the Preservation of

Ancient Buildings, and this owed a lot to the energy of

William Morris, the Society's secretary.

The slow, patient restoration of this building took the

best part of a century; indeed, when I first visited in

the 1980s I was still aware of a sense of decay.

Nothing could be further from the truth today. You step

into a wide, white, open space, one of England's great

church interiors. There, high above you, is the glorious

roof and the angels of God. The brick floors spread

around the scraped font, which still bears its dedicatory

inscription and standing places for participants. You

turn into the central gangway, and more than twenty empty

indents for brasses stretch before you. Dowsing can be

blamed for the destruction of hardly any of them. In

reality, you see the work of 18th and 19th century

thieves and collectors.

The bench-ends are superb. The benches themselves were

reconstructed in the late 19th century, supposedly from

the main post of Westleton windmill, but the ends are

some of the county's finest medieval images. There are

partial sets of basically three series: the Seven Deadly

Sins, the Seven Works of Mercy, and the Labours of the

Seasons. There are also angels bearing symbols of the

Holy Trinity and the Crown. There are other figures too,

obscure and fragmentary and whose purpose is unclear, as

if surviving figments of a broken dream. The quality of

what remains makes you grieve for what has been lost.

The rood screen is a disappointment; most of it is

modern, and the medieval bits perfunctory and scoured.

Having said this, note how tiny the exit from the north

aisle rood loft stair is. Also at this end of the church,

a scattering of medieval glass, mainly angels. There is

more in the south aisle, including a collection of

shields of the Holy Trinity:

. .

But step through the central aisle to see something

remarkable. The priest and choir stalls are fronted by

exquisite carvings of the Apostles, the Evangelists, John

the Baptist, St Stephen, Mary Queen of Heaven and Christ

in Majesty. Seeing these eighteen carvings is a bit like

gobbling up a very large box of chocolates, but it is

worth stopping to consider quite how genuine they all

are. For a start, there could not have been choir stalls

here in medieval times, and in any case we know that

these desks and their frontages were in the north aisle

chapel until the 19th century. They were used as school

benches in the 17th century; they still bear holes for

inkpots, and the graffiti of a bored Dutch child (his

father was probably working on draining the marshes) is

dated 1665. There is nothing at all like them anywhere

else in Suffolk.

Whatever, the east end of the

chancel and aisles are thrillingly modern, wholly

devotional. In the north aisle, traditionally the Hopton

chantry, extraordinary friezes of skeletons become

symbols of the four evangelists behind the altar. Beside

them is Peter Ball's beautiful Madonna and Child.

Separating the south aisle chapel from the sanctuary is

is one of Suffolk's biggest Easter sepulchres, tomb of

the Hoptons. Behind the high altar, branches arranged

like huge stag antlers spread dramatically. It is all

just about perfect. Tucked to one side of the organ is a

clockjack; Suffolk has two, and the other is down-river

at Southwold. They date from the late 17th century, and

presumably once struck the hours; at high church

Blythburgh and Southwold today, they are used to announce

the entry of the ministers.

This is a wonderful church

to wander around in, the light and the air

changing with the seasons, a suffused sense of

the numinous presenting its different faces

according to the time of day and time of year.

Come here on a bright spring morning, or in the

drowsy heat of a summer's day. Come on a cold

winter afternoon as the colours fade and the

smell of woodsmoke from neighbouring cottages

weaves a spell above the old stone floors and

woodwork. And before you leave, find the doorway

in the south-west corner of the nave. It opens

onto a low, narrow stairway. You can go up it. It

leads up into the parvise storey of the south

porch, now reappointed and dedicated as a tiny

chapel, a peaceful spot to spend a few moments

before continuing your journey.

You may be reading this entry in a far-off land;

or perhaps you are here at home. Whatever, if you

have not visited this church, then I urge you to

do so. It is the most beautiful church in

Suffolk, a wonderful art object, and it is always

open in daylight. It remains one of the most

significant medieval buildings in England. If you

only visit one of Suffolk's churches, then make

it this one. |

|

|

|

|

|