| |

|

|

|

My wife's mother Joan died.

Only a few months before, we had wandered

around the churchyard at Long Melford

visiting the graves of Joan's parents and

brothers, but she fell ill suddenly in

October, and at the start of November she

died peacefully in her sleep. It was All

Saints Day. It

was more than half a century since she

had been married in Long Melford church,

and more than forty since her daughter

Jacqueline was baptised there. This was

the family church, and that made it

special in a particular way, but Holy

Trinity is a special place in lots of

ways, of course. Easily the grandest

church in Suffolk, more feminine and

beautiful than its near rival Lavenham,

it was the only church in Suffolk to

receive five stars in Simon Jenkins'

sometimes controversial England's

Thousand Best Churches. Ignoring the

most un-Suffolk-like 20th Century tower,

the vast nave with its aisles and

clerestories is the crowning moment of

East Anglian Perpendicular, with which

only Salle in Norfolk can compete.

In 1960, when Joan had

married here, Long Melford was still an

industrial village with an ironworks and

other factories, but all that is gone

now. It is hard to see beyond a pleasant

picture postcard village, with its

antique shops along the long High Street

which stretches southwards from the

village green all the way to Sudbury. The

graves that sprawl eastwards of the

church are a reminder that ordinary lives

are led even in a place like this.

|

The

setting of Holy Trinity is superlative. At the

highest point and square onto the vast village

green, its southern elevation is punctuated by

the 16th Century Trinity Hospital almshouses.

Across the green is the prospect of Melford

Hall's pepperpot turrets and chimneys behind a

long Tudor wall. Another great house, Kentwell

Hall, is to the north. Kentwell was home to the

Clopton family, whose name you meet again and

again inside the church. Norman Scarfe described

it as in a way, a vast memorial chapel

to the family.

Holy

Trinity is the longest church in Suffolk, longer

even than Mildenhall, but this is because of a

feature unique in the county, a large lady chapel

separate from the rest of the church beyond the

east end of the chancel. The chapel itself is

bigger than many East Anglian churches, although

it appears externally rather domestic with its

triple gable at the east end. There is a good

collection of medieval glass in the otherwise

clear windows, as well as a couple of modern

pieces, and a very mdern altarpiece at the

central altar. Jacqueline's mother remembered

attending Sunday School in this chapel in the

1940s.

The

intimacy of the Lady Chapel is in great contrast

to the vast walls of glass which stretch away

westwards, the huge perpendicular windows of the

nave aisles and clerestories, which appear to

make the castellated nave roof float in air. An

inscription in the clerestory records the date at

which the building was completed as 1496. Forty

years later, it would all have been much more

serious. Sixty years later, it would not have

been built at all. A brick tower was added in the

early 18th Century, and the present tower, by GF

Bodley, was encased around it in 1903. As Sam

Mortlock observes, this tower might seem out of

place in Suffolk, but it nevertheless matches

the scale and character of the building. It

is hard to imagine the church without it.

I

came here back in May with my friend David

Striker, who, despite living thousands of miles

away in Colorado, has nearly completed his

ambition to visit every medieval church in

Norfolk and Suffolk. This was his first visit to

Long Melford, mine only the latest of many. We

stepped down into the vast, serious space.. There

was a fairly considerable 19th Century

restoration here, as witnessed by the vast sprawl

of Minton tiles on the floor, although perhaps

the sanctuary furnishings are the building's

great weakness. Perhaps it is the knowledge of

this that fails to turn my head eastwards, but

instead draws me across to the north aisle for

the best collection of medieval glass in Suffolk.

During the 19th century restoration it was

collected into the east window and north and

south aisles, but in the 1960s it was all

recollected here. Even on a sunny day it is a

perfect setting for exploring it.

The

most striking figures are probably those of the

medieval donors, who originally would have been

set prayerfully at the base of windows of

devotional subjects. Famously, the portrait of

Elizabeth, Duchess of Norfolk is said to have

provided the inspiration for John Tenniel's

Duchess in his illustrations to Lewis Carroll's Alice

in Wonderland, although I'm not sure there

is any evidence for this. Indeed, several of the

ladies here might have provided similar

inspiration.

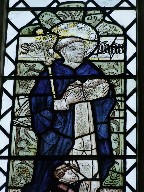

The

best glass is the pieta, Mary holding the body of

Christ the Man of Sorrows. Beneath it is perhaps

the best-known, the Holy Trinity represented in a

roundel as three hares with their ears

interlocking. An angel holding a Holy Trinity

shield in an upper light recalls the same thing

at Salle. Other glass includes a fine

resurrection scene and a sequence of 15th Century

Saints. There is also a small amount of

continental glass collected in later centuries,

including a most curious oval lozenge of St

Francis receiving the stigmata.

Walking

eastwards down the north aisle until the glass

runs out, you are rewarded by a remarkable

survival, a 14th century alabaster panel of the

Adoration of the Magi. It probably formed part of

the altar piece here, and was rediscovered hidden

under the floorboards in the 18th century.

Fragments of similar reliefs survive elsewhere in

East Anglia, but none in such perfect condition.

Beyond it, you step through into the north

chancel chapel where there are a number of

Clopton brasses, impressive but not in terribly

good condition, and then beyond that into the

secretive Clopton chantry. This beautiful little

chapel probably dates from the completion of the

church in the last decade of the 15th century.

Here, chantry priests would have celebrated

Masses for the dead of the Clopton family. The

chapel is intricately decorated with devotional

symbols and vinework, as well as poems attributed

to John Lidgate. The beautiful Tudor tracery of

the window is filled with elegant clear glass

except for another great survival, a lily

crucifix. This representation occurs just once

more in Suffolk, on the font at Great Glemham.

The panel is probably a later addition here from

elsewhere in the church, but it is still haunting

to think of the Chantry priests kneeling towards

the window as they asked for intercessions for

the souls of the Clopton dead. It was intended

that the prayers of the priests would sustain the

Cloptons in perpetuity, but in fact it would last

barely half a century before the Reformation

outlawed such practices.

You

step back into the chancel to be confronted by

the imposing stone reredos. Its towering

heaviness is out of sympathy with the lightness

and simplicity of the Perpendicular windows, and

it predates Bodley's restoration. The screen

which separates the chancel from the south chapel

is medieval, albeit restored, and I was struck by

a fierce little dragon, although photographing it

into the strong south window sunshine beyond

proved impossible. The brasses in the south

chapel are good, and in better condition. They

are to members of the Martyn family.

| The south chapel is also the

last resting place of Long Melford's

other great family, the Cordells. Sir

William Cordell's tomb dominates the

space. He died in 1581, and donated the

Trinity Hospital outside. His name

survives elsewhere in Long Melford: my

wife's mother grew up on Cordell Road,

part of a council estate cunningly hidden

from the High Street by its buildings on

the east side. At the west end of the

aisle is the towering 1930s cover to the

medieval font where her daughter would be

baptised. Before she died,

Joan asked that she should not be buried

among the family graves at Long Melford,

because they were too far from home, and

she thought it would make it difficult

for her husband to visit her there. If I

tell you that Joan and Bob lived off the

Melford Road in Sudbury, barely three

miles from the church, and in any case

Bob is a perfectly capable car driver, it

might give you an insight into how

parochial working class Suffolk still was

in the early years of the 21st century.

Instead, she chose to be buried in

Sudbury, within walking distance of the

family home. But anyone who knew her well

would tell you that she was really a

Melford girl at heart.

|

|

|

|

|

|