|

|

I kept

meaning to come back to Southwold

- the church, I mean, for I found

myself in the little town from

time to time. I finally kept my

promise to myself in the summer

of 2017, tipping up on a

beautiful sunny day only to find

the church closed for extensive

repairs. The days got shorter,

and by the time the church

reopened it was too late in the

year for me to try again. In

fact, it was not until late

October 2018 that I made it back

there, on another beautiful day.

Southwold is well-known to people

who have never even been there I

suppose, signifying one side of

Suffolk to which Ipswich is

perhaps the counter in the

popular imagination. Some thirty

years ago, the comedian Michael

Palin made a film for television

called East of Ipswich.

It was a memoir of his childhood

in the 1950s, and the basic comic

premise behind the film was that

in those days families would go

on holiday to seaside resorts on

the East Anglian coast. In the

child Palin's case, it was

Southwold.

The amusement came from the idea

that people in those days would

sit in deckchairs beside the grey

north sea, or shelter from the

drizzle in genteel teashops or

the amusement arcade on the pier.

In the Costa Brava package tour

days of the 1980s, the quaintness

of this image made it seem like

something from a different world. |

I remember Southwold in the

1980s. It was one of those agreeable

little towns distant enough from anywhere

bigger to maintain a life of its own. It

still had its genteel tea shops, its

dusty grocers, its quaint hotels and pubs

all owned by Adnams, the old-fashioned

and unfashionable local brewery. In the

white heat of the Thatcherite cultural

revolution, it seemed a place that would

soon die on its feet quietly and

peaceably.

And then, in the 1990s, the colour

supplements discovered the East Anglian

coast, and fell in love with it. The new

fashions for antique-collecting, cooking

with local produce and general country

living, coupled with a snobbishness about

how vulgar foreign package trips had

become, conspired to make places like

Southwold very sought after. Before Nigel

Lawson's boom became a bust, the inflated

house prices of London and the home

counties gave people money to burn. And

in their hoards, they came out of the big

city to buy holiday homes in East Anglia.

Although they are often lumped together,

the coasts of Norfolk and Suffolk are

very different to each other

(Cambridgeshire and North Essex are also

culturally part of East Anglia, but the

North Essex coast is too close to London

to have ever stopped being cheap and

cheerful, and Cambridgeshire has no

coastline). Norfolk's beaches are wide

and sandy, with dunes and cliffs and rock

pools to explore. Towns like Cromer and

Hunstanton seem to have stepped out of

the pages of the Ladybird Book of the

Seaside. Tiny villages along the

Norfolk coast have secret little beaches

of their own.

Suffolk's coast is wilder. Beaches are

mainly pebbles rather than sand, and the

marshes stretch inland, cutting the coast

off from the rest of the county. Unlike

Norfolk, Suffolk has no coast road, and

so the settlements on the coast are

isolated from each other, stuck at the

ends of narrow lanes which snake away

from the A12 and peter out in the

heathland above the sea. There are fewer

of them too. It is still quicker to get

from Walberswick to Southwold by water

than by land. Because they are isolated

from each other, they take on individual

personalities and characteristics.

Because they are isolated from the land,

they become bastions of polite

civilisation.

Between Felixstowe in the south, which no

outsiders like (and consequently is the

favourite of many Suffolk people) and

Lowestoft in the north, which is

basically an industrial town-on-sea (but

which still has the county's best beaches

- shhh, don't tell a soul) are half a

dozen small towns that vie with each

other for trendiness. Southwold is the

biggest, and today it is also the most

expensive place to live in all East

Anglia. Genteel tea shops survive, but

are increasingly shouldered by shops that

specialise in ski-wear and Barbour

jackets, delicatessens that stock

radicchio and seventeen different kinds

of olive, jewellery shops and kitchen

gadget shops and antique furniture shops

where prices are exquisitely painful.

Worst of all, the homely, shabby,

smoke-filled Sole Bay Inn under the

lighthouse has been converted by the

now-trendy Adnams Brewery into a chrome

and glass filled wine bar.

If you see someone in Norfolk driving a

truck, they are probably wearing a

baseball cap and carrying a shotgun. in

Suffolk, they've more likely just bought

a Victorian pine dresser from an antique

shop, and they're taking it back to

Islington. Does this matter? The fishing

industry was dying anyway. The tourist

industry was also dying. If places like

Southwold, Aldeburgh and Orford become

outposts of north London, at least they

will still provide jobs for local people.

But the local people won't be able to

afford to live there, of course. They'll

be bussed in from Reydon, Leiston and

Melton to provide services for people in

holiday cottages which are the former

homes they grew up in, but can no longer

afford to buy. Does this seriously annoy

me? Not as much as it does them, I'll

bet.

So, lets go to Southwold, turning off the

A12 at the great ship of Blythburgh

church, the wide marshes of the River

Blyth spreading aimlessly beyond the

road. We climb and fall over ancient

dunes, and then the road opens out into

the flat marshes, the town spreads out

beyond. We enter through Reydon (now

actually bigger than Southwold, with

houses at half the price) and over the

bridge into the town of Southwold itself.

Having been so

critical, I need to say here that

Southwold is beautiful. It is quite the

loveliest small town in all East Anglia.

None of the half-timbered houses here

that you find in places like Long Melford

and Lavenham. Here, the town was

completely destroyed by fire in the 17th

century, and so we have fine 18th and

19th century municipal buildings. One of

the legacies of the fire was the creation

of wide open spaces just off of the high

street, called greens. The best one of

all is Gun Hill Green, overlooking the

bay where the last major naval battle in

British waters was fought. The cannons

still point out to sea. The houses here

are stunning, gobsmacking, jaw-droppingly

wonderful. If I could afford to buy one

of them as a weekend retreat, then you

bet your life I would, and to hell with

the people who moaned about it.

At the western end of the High Street is

St Bartholomew's Green, and beyond it

sits what is, for my money, Suffolk's

single most impressive building. This is

the great church of St Edmund, a vast

edifice built all in one go in the second

half of the 15th century. Only Lavenham

can compete with it for scale and

presence. Unlike the massing at St Peter

and St Paul at Lavenham, St Edmund is

defined by a long unbroken clerestory and

aisles beneath - where St Peter and St

Paul looks full of tension, ready to

spring, St Edmund is languid and

floating, a ship at ease.

Southwold church was just one of several

vast late medieval rebuildings in this

area. Across the river at Walberswick and

a few miles upriver at Blythburgh the

same thing happened. Blythburgh still

survives, but Walberswick was derelicted

to make a smaller church, as were

Covehithe and Kessingland. Dunwich All

Saints was lost to the sea. But Southwold

was the biggest. Everything about it

breathes massive permanence, from the

solidity of the tower to the turreted

porch, from the wide windows to the

jaunty sanctus bell fleche.

Along the top of the aisles, grimacing

faces look down. All of them are

different. The pedestals atop the

clerestory were intended for statues as

at Blythburgh, but were probably never

filled before the Reformation intervened.

At the west end, above the great west

window, you can see the vast inscription SAncT

EDMUND ORA P: NOBIS ('Saint Edmund,

pray for us') as bold a record of the

mindset of late medieval East Anglian

Catholicism as you'll find.

As at Lavenham and

Long Melford, the interior has been

extensively restored, but not in as heavy

or blunt a manner as at those two

churches. St Edmund has, it must be said,

benefited from the attentions of German

bombers who put out all the dull

Victorian glass with blast damage during

World War II. Here, the interior is vast,

light and airy, and much of the

restoration is 20th century work, not

19th century.

Perhaps because of this, more medieval

interior features have survived. Unlike

Long Melford, Southwold does not have

surviving medieval glass (Mr Dowsing saw

to that in 1644), but it does have what

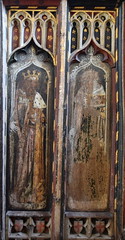

is the finest screen in the county.

It stretches right the way across the

church, and is effectively three separate

screens. There is a rood screen across

the chancel arch, and parclose screens

across the north and south chancel

aisles. All retain their original dado

figures. There are 36 of them, more than

anywhere else in Suffolk. They have been

restored, particularly in the central

range, but are fascinating because they

retain a lot of original gesso work,

where plaster of Paris is applied to wood

and allowed to dry. It is then carved to

produce intricate details.

The central screen shows the eleven

remaining disciples and St Paul. They

are, from left to right, Philip,

Bartholomew, James the Less, Thomas,

Andrew, Peter, Paul, John, James, Simon,

Jude and Matthew.

The south chancel chapel is

light and open. The bosses above are said

to represent Mary Tudor and her second

husband Charles, Duke of Brandon. The

screen here is painted with twelve Old

Testament prophets, and Mortlock suggests

that they are by a different hand to the

images on the other two screens. Here on

the south screen, some of the figures

have surviving naming inscriptions, and

Mortlock surmises that the complete

sequence, from left to right, is Baruch,

Hosea, Nahum, Jeremiah, Elias, Moses,

David, Isaiah, Amos, Jonah and Ezekiel.

Further, he observes that the subject is

a usual one for the English Midlands, but

rare for East Anglia, and that perhaps

this part of the screen came from

elsewhere. The same may be true of the

other two parts - it is hard to think

that the central screen was deliberately

made too wide for the two arcades.

The north aisle chapel is

reserved as the blessed sacrament chapel,

and its screen is probably the most

interesting of the three. This screen is

harder to explore, because the northern

side is curtailed by a large chest, but

it features angels. Unlike the screens at

Hitcham and Blundeston, which show angels

holding instruments of the passion, these

are the nine orders of angels, with

Gabriel at their head, and flanked by

angels holding symbols of the Trinity and

the Eucharist. Mortlock says that they

are so similar to the ones at Barton Turf

in Norfolk that they may be by the same

hand, in which case the central screen is

also by that person. They are, from left

to right, the Holy Trinity, Gabriel,

Archangels, Powers, Dominions, Cherubim,

Seraphim, Thrones, Principalities,

Virtues, Messengers, and finally the

Eucharist. The Holy Trinity angel still

has part of the original dedicatory

inscription beneath his feet.

If part or all of this

screen came from elsewhere, where did it

come from? Possibly either Walberswick,

Covehithe or Kessingland, the three

downsized churches mentioned earlier.

More excitingly, it might have come from

one of the churches along this coast that

was lost to the sea, perhaps neighbouring

St Nicholas at Easton Bavents, or, just

to the south, St Peter or St John the

Baptist, the two Dunwich churches lost in

the 16th and 17th centuries. We'll never

know.

If you turn back at the screen and face

westwards, your eyes are automatically

drawn to the towering font cover, part of

the extensive 1930s redecoration of the

building. The clerestory is almost like a

glass atrium intended to house it. Also

the work of the period is the repainting

and regilding of the 15th century pulpit

(a lot of people blanch at this, but I

think it is gorgeous) and the lectern.

Beneath the font cover, the font is

clearly one of the rare seven sacraments

series, and part of the same group as

Westhall, Blythburgh and Wenhaston. As at

Blythburgh and Wenhaston, the panels are

completely erased, probably in the 19th

century, an act of barbarous vandalism.

Given that Westhall is probably the best

of all in the county, we must assume that

three major medieval art treasures were

wiped out. Astonishingly, vague shadows

survive of the former reliefs; you can

easily make out the Mass panel, facing

east as at Westhall, the Penance panel

and even what may be the Baptism of

Christ.

Stepping through the screen, the reredos

ahead is by Benedict Williamson and the

glass above by Ninian Comper, familiar

names in the Anglo-catholic pantheon, and

evidence of an enthusiasm here that still

survives in High Church form. The Comper

east window depicts St Edmund in his four

guises as youth, king, martyr and saint,

an interesting idea, but it is perhaps

not the best executed window in the

Comper canon. There is a good engraved

glass image of St Edmund to the north of

the sanctuary by John Hutton, placed here

in 1971, very much of its period. As

James Bettley notes in the revised

Pevsner, it is better seen from the

outside. On the wall of the chancel to

the west of it, the high organ case is

also painted and gilded enthusiastically.

As well as the screen, Southwold's other

great medieval survival is the set of

return stalls either side of the eastern

face of the chancel screen. The bench

ends feature the kneeling donors in

profile, and there are misericord seats,

but the best features are the handrests

between the seats. On the south side,

carvings include a man with a horn-shaped

hat and sinners being drawn into the

mouth of hell. On the north side are a

man playing two pipes, a monkey preaching

and a beaver biting its own genitals, a

tale from the medieval bestiary,

apparently.

What else is there to see?

Well, the church is full of delights, and

rewards further visits which always seem

to turn up something previously

unnoticed. St George rides full tilt at a

dragon on an old chest at the west end of

the north aisle. There is good 19th

century glass in the porch and at the

west end of the nave. A clock jack

stands, axe and bell in hand, at the west

end, a twin to the one upriver at

Blythburgh. This one has a name, he's

called Southwold Jack, and he is one of

the symbols of the Adnams brewery.

As Mortlock notes, there are very few

surviving memorials. This is partly

because St Edmund was not in the

patronage of a great landed family, but

it may also suggest that they were

largely removed at the time of the 19th

century restoration, as at Brandon. One

moving one is for the child of a vicar,

and there are some interesting pre-Oxford

Movement 19th century brasses in the

south aisle.

High, high above all this, the roofs are

models of Anglo-Catholic melodrama, the

canopy of honour to the rood and the

chancel ceilure in particular. But there

is a warmth about it all that is missing

from, say, Eye, which underwent a similar

makeover. This church feels full of life,

and not a museum piece at all. I remember

attending evensong here late one winter

Saturday afternoon, and it was magical.

On another visit, I came on one of the

first days of spring that was truly warm

and bright, with not a cloud in the sky.

As we drove into town, a cold fret off of

the sea was condensing the steam of the

brewery, sending it in swirls and skeins

around the tower of St Edmund like low

cloud. It was so atmospheric that I

almost forgave them for what they have

done to the Sole Bay Inn.

|