| |

|

|

|

I am very much ashamed to

say that when I first wrote about this

church in the summer of 2002, I was led

into temptation to mess about a bit. It

was something like the 300th church on

the site, and I'd discussed with a

journalist friend the dangers of the site

becoming formulaic, a listing of external

and internal features, the occasional

photograph. This was in the days before I

embraced digital photography, of course.

He suggested, as a joke, that perhaps I

could try writing them in the style of

different authors, and we settled on a

list of James Joyce, Marcel Proust,

Ernest Hemingway and Micky Spillane as

the writers with styles most easy to

replicate. Well, Hemingway and

Spillane never got done, but Joyce and

Proust did. St Mary's was the Joyce

entry, although it would be truer to say

that it was a pastiche of his 1916 work Ulysses.

I thought it would be a harmless piece of

fun, given that St Mary is redundant so

the parish were unlikely to be offended,

and in any case I didn't think anyone

actually read what I wrote.

As it turned out, I was

wrong. They did. Lots of people contacted

me about it, but as the response, on the

whole, was positive, I left it, and left

it, meaning to go back to St Mary and

rewrite it after I acquired a digital

camera in 2003. Unfortunately, it has

taken until 2016 for me to make that

journey. Sorry, Bungay. Sorry, Joyce.

|

St

Mary is quite the grandest redundant medieval

church in Suffolk. The tower, of 1475, is one of

the most spectacular Perpendicular moments in a

county not short of them. What remains to the

east of it was the parochial nave of a

Benedictine convent established in Bungay in the

late 12th Century. The ruins beyond were

conventual buildings, including the nun's choir

which stood to the east of the nave. At the

dissolution it became the parish church, but was

gutted in the great Bungay fire of 1688. Thus,

the interior is entirely post-Reformation in

content and character. There were successive 19th

Century restorations, one led by Thomas Jekyll as

at neighbouring Holy Trinity, another later in

the century by that safe pair of hands Richard

Phipson, the diocesan architect.

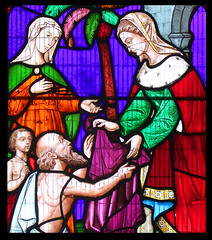

Because

of this, interest in the interior rests largely

on two things, the civic memorials and the 19th

Century glass, both very good of their kind.

Jekyll's restoration saw the installation of

windows by Charles and Alexander Gibbs.

Unfortunately, that in the west window has not

survived other than Alexander Gibbs's typically

fizzy orange lozenges in the tracery of the upper

lights. But the east window of the north aisle

does survive, and depicts the Works of Mercy.

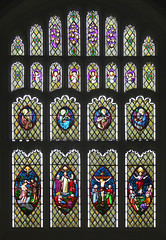

If

the Gibbs brothers' work in the north aisle is

vibrant, the east window is restrained and

elegant. It is a window of two halves, the upper

lights featuring Powell & Sons' jolly angels,

the lower lights four scenes in the Life of

Christ and more angels by Thomas Baillie.

Presumably Baillie was also responsible for

setting the Powell angels in the flowery quarries

used in his own window.

The memorials

include the Norwich sculptor Thomas Rawlins the

Younger's elegant 1760 monument for Henry

Williams; a monument to Pergrina Browne by

Rawlins's father as well as several other

monuments of the 18th century, mostly by Norwich

workshops. The only other furnishings of interest

are an 18th Century font, installed here as at

Holy Trinity after the fire, and a dole cupboard

of 1675 signed with a rebus, the letter Q and a

rat, to show it was given by a curate. It may not

have come from here originally, as the initials

of the man do not match anything in the records

here.

| An interior and an exterior

of different significances then.

Internally it is not a dull church, but

St Mary's great glory is of course its

exterior, as at St Michael in

neighbouring Beccles which also suffered

a serious fire. Here, there are plenty of

details to spot and wonder at. What, for

example, do you make of the reliefs in

the spandrels of the north porch? One

appears to show a lion and a man - is he

killing the lion, or is the lion eating

him? The other, in some ways more

mysterious, shows a lion with a cat, or

possibly a lion cub. There are several

excellent grotesques along the north side

of the building, including one man

holding his mouth open as if suffereing

an attack of toothache, and at the north

east corner is a man kneeling to pray,

but apparently supporting the building on

his back - a patron, perhaps? So

there we are, I went back to St Mary at

last, and I can put that Joyce pastiche

to rest, although you can still read the

text (though not the photographs that

went with it) here.

And the Proust entry? Well, you'll just

have to find it.

|

|

|

|

|

|