| |

|

The River Stour forms most

of the border between Suffolk and Essex, and on

either side are some of England's loveliest

villages. On a hot summer's day, Cavendish with

its wide green, its medieval cottages and ancient

inns, its pretty church in its tight tree-lined

churchyard, is a fine place to be. This is the

antithesis of the copses and fields which form

the setting for so many of Suffolk's churches,

for this is England tamed and civilised, and the

sheer Englishness of the setting, especially when

seen from behind a pint outside the pub, can

inspire mild feelings of patriotism in even the

dourest globalist. No wonder Americans love

Cavendish so much. One American who loved

Cavendish was John Appleby, whose book A

Suffolk Summer has become more elegiac as

the years go by. He was an American serviceman

stationed near Cavendish, and in the year the

Second World War ended he made a series of

journeys around Suffolk while he waited to be

demobbed, and it is worth reading if only to see

how busy these quiet Stour Valley villages were

in those days.

There

was great wealth here in the late Middle Ages,

and this built the substantial exterior of St

Mary. The church we see today began to come

together in the early 14th Century, when the

great tower was erected against an earlier

church. In 1381 Sir John Cavendish left the

enormous sum of £40 to the building of a new

chancel, which presumably was enough to pay for

it in entirety. As it turns out this was one of

the less likely, and perhaps more fortunate,

outcomes of the Peasants' Revolt, for Sir John

had been lynched on the grounds that it was his

son who had Wat Tyler put to death, the

parishioners of Cavendish reaping the benefits of

his demise.

This

was only the first of a number of bequests

recorded by Peter Northeast and Simon Cotton,

which in their way tell the story of the church's

construction. In 1471 Richard Cagge left money to

the fabric of the new aisle to be made on the

south side of the church, while in 1483 John

Smyth left £20 to the making of the coorce

of the said church of Cavendish, thus the

nave was being rebuilt at this time. Thereafter

there are a number of bequests for furnishings,

suggesting that the church was structurally

complete by then, with the icing on the cake

being Thomas Goldyinge's bequest in English of

1504 which states that I bequeth of my goodes

and catalles asmoch mony as conveinently will

serve to the beiyng of a newe tenoure belleto be

according in true musike unto the iiii belles

nowe hangyng in the steple of Cavendiish

aforesaid.

You

step into a church which is bright, neat and full

of light. It is larger than you might expect when

approaching the south porch through the tight

churchyard. There is very little coloured glass,

and the crispness of an early 21st Century

makeover allows a real appreciation of the

structure. It is a fine setting for several

interesting details. The 15th Century font came

as part of the new nave, but the most striking

feature which faces you across the church from

the north aisle was not originally from this

church at all. This is a large canopied reredos

by Ninian Comper, made in 1895 for the private

chapel in London of Athelstan Riley and brought

here after his death. The central part of the

reredos is a 16th Century Flemish panel,

presumably once part of an altarpiece, depicting

an animated Crucifixion with plenty of figures

milling around beneath including Roman soldiers

casting lots for Christ's garments. The gilded

figures beneath are Comper's.

The reredos is

one of several reminders of an Anglo-Catholic

enthusiasm here in the early part of the 20th

Century, and the late Sam Mortlock bemoaned that

the reredos was no longer in use in the chancel,

considering that it had been reduced to the

status of an artifact by being placed on

display in the nave, but it must be said that the

clean, clear space of the chancel manages well

without it. Another reminder of that early 20th

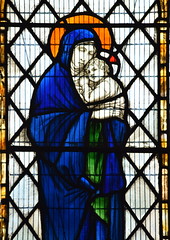

Century enthusiasm is across in the south aisle

where a very good window of 1922 depicts the

Blessed Virgin and Christchild flanked by angels.

It remembers Emmeline Fanny Edmonds and asks in

Latin for prayers for her soul. It's the work of

Clement Skilbeck and is, I think, his only work

in Suffolk although there is some over the border

in Cambridgeshire. The Journal of Stained

Glass Glass House Special notes a letter

which survives in the archives from the Glass

House at Fulham quoting for a three-light window

but commenting that the sketch is rather

vague as to how much background painting there

will be. Fortunately, in the event there

would be hardly any, leaving us with this

charming period piece. It is interesting to note

from the inscription in the glass that Miss

Edmonds had died on the 6th February 1922 and the

letter, which is obviously a reply to a

commission, is dated 9th March 1922. This seems a

remarkably short period of time, so perhaps she

had left instructions in her will for the window

having previously arranged its installation with

the parish.

At

the east end of the south aisle is the tomb chest

for Sir George Colt, who died in 1570. At this

time, our English churches were still in a

ferment, and until the late 1530s a chantry altar

had probably stood here, perhaps for a guild. You

can still see the squint that allowed the

celebrant in the chapel a view of the high altar,

necessary because a side chapel Mass could not

begin until the high altar Mass was underway. The

canopied niche to the right of the chest contains

a modern image of the Madonna and child, and may

very well have contained something similar until

the 1530s. Colt's tomb, and its placement in such

a sacred space, must have sent a clear message to

the people of Cavendish that their old religion

was over. Stepping up into the light of the

chancel, you can look up to see Cavendish's best

medieval survival. This is the canopy of honour

over the sanctuary dating from the end of the

14th Century and carefully restored in the 1860s.

Silvered oak faces stare out from panels

decorated with wild flowers.

A

large roundel memorial in the south aisle

remembers the two most famous recent residents of

this parish, Baroness Sue Ryder and Baron Leonard

Cheshire. They are best known for their war

relief work in the years after 1945. Cheshire had

won the Victoria Cross for his bravery as a

bomber pilot, whilst Ryder had worked as a young

woman in the ruins of Nazi-devastated Warsaw.

They were extraordinary people who gave

themselves completely to the relief of the

suffering of others, living Christ's command to

welcome the stranger, care for the sick and

comfort the dying. They received their honours

quite separately, Ryder becoming Baroness Ryder

of Warsaw in 1979 and Cheshire becoming Baron

Cheshire in 1991, an event which made his wife a

baroness twice over. Their most visible legacies

are the Sue Ryder charity, Sue Ryder Homes and

Cheshire Homes. The Catholic Diocese of East

Anglia (Ryder and Cheshire were both Catholics)

has recently begun a process with a view to

Cheshire's beatification.

|

|

|