| |

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

I had not

been back to Eye church for years. I had often passed

through the town, often stopped here indeed, but the

church was such a big project I had usually carried on to

somewhere else. I finally tipped up here on the first

Sunday in September 2018, a few minutes after High Mass

had finished. The great church was full of incense, the

bright summer light thrusting through it, claiming the

interior for something greater and more numinous than

mere congregational worship.

Eye is

perhaps the most robustly independent of Suffolk's

smaller towns. It isn't big at all, but it is far from

anywhere else of any size in the county, if you ignore

Norfolk's Diss looming on the horizon. The railways

reached it, bringing with them proud 19th century

municipal buildings. Until the 1830s, the town returned

two members to parliament, and it still gave its name to

the parliamentary constituency until the 1970s. There is

a castle (or, at least, what looks like a castle), some

decent pubs, a theatre, and one of Suffolk's grandest

churches.

The great flint-encrusted tower of St Peter and St Paul

rises above a memorably crafted interior. Here inside, we

will find the nearest thing Suffolk has to a fulfilment

of the ecclesiological aspirations of our

great-grandparents' generation.

From a tiny spark, a glint in the eye of John Keble at

Oxford in the 1830s, the sacramental revival in the

Church of England spread like wildfire over the course of

the ensuing century. The Church set about rediscovering

its Catholic roots, and the preaching houses of the

Hanoverians were stripped bare and filled with all the

best that the Gothic revival had to offer. In many

medieval churches, original artefacts were rediscovered

and pressed back into service. Where this wasn't

possible, the mass-production workshops of Birmingham and

London could be called upon to provide what history could

not.

Ironically, the catalyst for all this had been some of

those very reform acts which had deprived Eye of its

'rotten borough' status. Catholic emancipation in the

1820s had been followed by grants to a Catholic

university in Ireland. Keble, along with Pusey, Newman,

Froude and the others, saw that the Church of England was

in danger of being sidelined as a protestant sect. The

Oxford Movement, as it became known, published a series

of tracts to try and educate the middle classes about

their lost past. Their intention was that the Church

would recover its catholicity, and its destiny as a

national church, but the inevitable result was that some

of the Movement, Newman among them, would leave the

Church of England to become Catholics themselves.

The medieval Church that they most admired was that of

the early 14th century. This allowed them to see the

later medieval period as a decline, an abuse-riddled

downturn, from which the Church had to be rescued at the

Reformation. However, as the Movement went on, there were

many who asked if the Reformation had really been

necessary at all.

The grandeur of Suffolk's biggest churches on the eve of

the Reformation was a direct result of the county being

the late medieval industrial heartland of England. Here

at Eye that wealth rebuilt the tower in the second half

of the 15th century. The same masons were working at

Laxfield and on the near-identical tower at Redenhall,

over the Norfolk border. As at Redenhall, it was De la

Pole money that rebuilt it, and the family arms are

discernible still. Most spectacularly, high up on the

south side of the tower top stands St Michael the

archangel, overseeing it all.

Sam Mortlock

points out that you can see the shape of the windows

change from late-Decorated to Perpendicular over the

course of the 40 years or so it took to build. You can

see the last windows, the pure rationalism of the late

Perpendicular period, right at the top in the bell-stage.

Beneath are some more mystical Decorated windows, and

below them the vast west window which bridges the gap

between the two.

As the tower was being completed, so the rest of the

church was undergoing an opulent rebuild. You can see

evidence of the extension at the east end of the south

aisle, where a blocked door sits beside the new one into

the chancel. As at Lavenham, the parishioners here were

left in no doubt about the rise of secular power and its

might. Soon, the De la Poles, the Springs, the De Veres

and so on would outgrow the middle ages, and the

aspirations of wealthy families such as these would give

rise to the Reformation, the nation state, and ultimately

capitalism itself.

This was in the future. For now, the De la Poles invested

in prayers as well as commerce, and although their south

porch is a bit battered these days, it remains one of the

loveliest in Suffolk, its brickwork echoing the gildhall

on the other side of the church. You can only enter it

from inside the church if you hope to see the dole table

and fine 13th century doorway that survives of the

earlier church, and you have to be there when it is open,

for it now contains a shop.

Externally then, this is one of the great East Anglian

churches. Here we see the late medieval Church in all its

glory.

But in the 1530s, a collision of expediency and

opportunity put an end to it all. Henry VIII took the

Church out of Europe. His son Edward VI enforced its

protestant credentials, and Edward's sister Elizabeth I

settled the whole thing by imposing the Elizabethan

Settlement, a suppression of the old ways, to bolster her

grip on power. The past was subverted and lost, first as

Anglicans, and then as Puritans, we overthrew the

religion of our parents and grandparents, of the long

English generations. We all but obliterated the old

order, the ancient faith. Much was lost which was dear to

us, and much was forgotten which we had believed to be

true. This was what the Oxford Movement tried to recover,

but in the context of a national established church, with

spectacular results.

By the end of the 19th century, the Anglo-catholic

movement was in the ascendant. Most churches now saw Holy

Communion as the main service rather than Morning Prayer.

Most churches returned their focus to the altar rather

than the pulpit. Perhaps the formality and splendour of

the high church aesthetic chimed with the pomposity and

rhetoric of British imperialism, for it is worth noting

that the rise and fall of Anglo-Catholicism as a

mainstream tradition coincided almost exactly with the

growth and decline of the British Empire. The movement

reached its height in the early years of the 20th

century, and probably the greatest exponent of

Anglo-catholic fixtures and fittings was Ninian Comper.

Comper, who will be familiar to many in Suffolk for his

work at Lound and Kettlebaston, at Ipswich St Mary Elms

and Ufford, all beacons of early 20th century

Anglo-Catholic correctness.

All disappearing now, alas. The ritualist tide has

receded almost completely, and only the trappings and

debris survive here and there, a reminder of what once

was. An age that hovers on the edge of a public memory,

when the formal vision of the established Church was at

the heart of British daily life, an age of candles and

incense, of richly coloured vestments and four-part

choirs. An age of anthems, and war memorials, and

processions, and coronations, and a liturgy that brought

you to your knees.

But in some places some of this still survives. Here at

Eye the tradition has not completely receded.

You walk beneath the great tower with its wonderful

fan-vaulting so uncharacteristic of Suffolk, and then

into the open space of a large, civic church. As at

Hadleigh, Halesworth, and other small Suffolk towns, the

19th century restoration here was pretty significant.

However, into this created space have been placed

furnishings of superb quality and design. The centre

piece is Comper's magnificent rood loft, built on the

remains of the medieval screen in the mid-1920s. The

screen below is perhaps not as good in its way as some of

the county's other late-15th century screens, but in any

case pales slightly beneath the loft, which is easily the

best 20th century work of its kind in Suffolk.

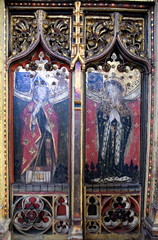

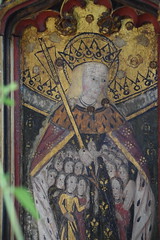

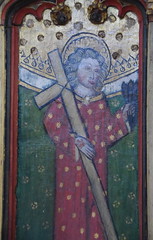

The figures on the dado screen must have been painted in

about 1500, which is to say rather later than most East

Anglian screens. Pevsner thought that they were all

bad. It is true that they are doll-like, with

nothing like the sophistication of those across the A140

at Yaxley, for example, but they have a certain naive

charm. Perhaps they are symptomatic of the decay in

English art towards the end of the medieval period.

Curiously, the gessowork that forms a relief to the

figures is really quite sophisticated. They are, from

north to south: I: St Paul, II: St Helen, III: St Edmund,

IV: St Ursula and her eleven thousand virgins, V: Henry

VI, VI: St Dorothy, VII: St Barbara, VIII: St Agnes, IX:

St Edward the Confessor, (the gap into the chancel is

here), X: St John the Evangelist, XI: St Catherine, XII:

St William of Norwich, XIII: St Lucy, XIV: St Thomas of

Canterbury, and XV: St Agatha.

Many of these

Saints had strong local cults in the late medieval

period, and are familiar from other East Anglian screens.

The less common St William of Norwich adds a little

colour, standing as evidence of an anti-semitism that

persisted well into the late middle ages, despite (or

perhaps because of) the fact that the Jewish population

had been expelled some two centuries previously. Two of

the other images resonate strongly - the cults of Henry

VI and St Thomas of Canterbury were particularly frowned

upon by the 16th century reformers.

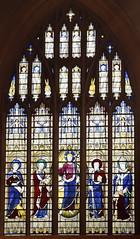

Up in the chancel, an entirely secular memorial recalls

the Reverend Thomas Wythe, for fifty years Vicar of this

Parish. he died in 1835, and the monument notes that he

cordially believed, zealously preached, assiduously

practiced. It is unlikely that the Reverend Wythe

would recognise the inside of his church today. Much of

what was foregrounded in this church by the considerable

1850s restoration was further adapted and enhanced by the

higher church over the ensuing century. The most

spectacular work is by Ninian Comper. As well as the rood

and rood loft already mentioned, he produced the great

east window depicting the Risen Christ flanked by St

John, St Peter, St Paul and St Polycarp in memory of John

Polycarp Oakey, parish priest here who died in 1926.

Oakey oversaw

the Anglo-catholic revival here with the help of Maude

Tacon of Brome Hall, who was patroness of the living and

also, it seems, Oakey's lover. Comper was a close friend

of the Tacon family, and even designed Maude Tacon's

memorial in Eye Cemetery when she died. Comper's also is

the towering font cover, and the window of St George in

the north aisle in memory of George Gerald Warnes, a

'Black-and-Tan' auxiliary who was gunned down by the IRA

in Grafton Street, Dublin during the so-called 'Troubles'

that preceded the Irish Civil War of the 1920s.

The process continues. The elegant tomb recess in the

north aisle, for example, is host to Lough Pendred's

1960s Madonna and child. Pendred carved the same subject

in a different composition for the lady chapel in the

south aisle. To be honest, this kind of light wood

romantic abstraction is very much of its decade, but

there is a poignancy to its presence here in one of the

surviving outposts of modern Anglo-Catholicism. Eye is

one of the few Suffolk churches that still 'sports the

big six'; that is to say, has six tall candles on the

high altar.

Comper decorated the chancel roof, which glows

magnificently in the morning light through the east

window. Tucked away in two corners are two

post-Reformation tombs to Nicholas Cutler and William

Honyng, the first in the north aisle (it was originally

in the sanctuary, according to Mortlock) and the second

in the south aisle chapel. They are curious, because they

appear to be almost identical, although whether this is a

tribute to early-modern vanity or mass-production I

couldn't say.

This is a church in which to wander. It is full of

interest, little details and quiet corners. A bit like

Eye itself. Beside the church, the large, half-timbered

building to the north is the former guildhall. For a long

time this was a wonderful second hand bookshop, but that

is now closed. On the corner post are the restored angels

of the Annunciation - one only has been left unrestored.

Perhaps it can stand as the symbol for this splendidly

reinvented church.

Simon Knott, September 2018

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|