| |

|

|

|

This pleasant little church

sits out on the edge of a straggle of

suburbia to the south of Bury St Edmunds,

Great Whelnetham running into

Sicklesmere, which gives its name to the

ancient Hundred, but has no parish church

of its own. The church is entirely in the

Essex style, although we are still a good

ten miles from the border here. The

churchyard is secluded, setback behind

the village school, a green velvet bed

for a jewel of a church on the morning in

late summer 2014 that I most recently

visited. Sam Mortlock found it

depressing on his visit in the 1980s, but

the grim pebbledash he mentions has been

repainted on the nave at least, and it

presents a pretty prospect to the south.

There probably never was a tower,

although a 15th century bequest left

money for one. In any case, evidence

remains of the Norman, and possibly

Saxon, origin of this church. The little

clerestory is delightful, like the

windows in the upper storey of a cottage.

As

so often with churches of this kind, St

Thomas of Canterbury seems larger inside

than out, a feeling enhanced by the lack

of clutter and the bright light inside.

The chancel has been cleared of

furnishings, a north transept neatly

arranged with modern chairs. The transept

was added in 1839, an early date and

suggesting it was built for increased

capacity rather than liturgical reasons.

Its domestic window tracery and small

chimney add to the sense of this being a

cottage as much as a church. A tapestry

of the Annunciation hangs in the

transept, and generally there is an air

of simplicity about the nave and its

transept. A lot happened here in the 19th

and 20th Centuries, but stil the Norman

lancets remain to remind us of how long

this serious house has been here.

Everything is well looked after and

obviously loved.

|

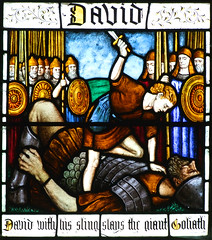

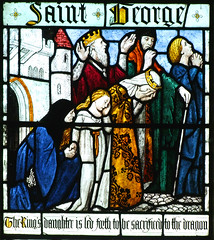

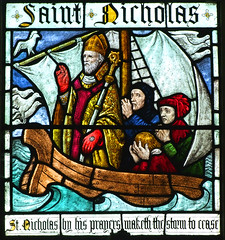

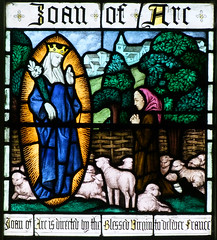

It

is obvious too that this church had

Anglo-catholic sympathies early in the 20th

Century, and surviving evidence includes the

rather extraordinary east window. It is by

Burlison & Grylls, and forms the parish war

memorial. From left to right, it depicts the boy

David, St George, St Nicholas and Joan of Arc, an

eclectic mix to find in an English country parish

church, especially Joan of Arc who is rarely

depicted in Anglican churches (although, quite by

coincidence, I came across another representation

of her later in the week at St Sepulchre on

London's Holborn Viaduct). Scenes in the story of

each are under their feet.

Fragments

of medieval glass survive, and the most haunting

is a fragment of a 15th Century nativity scene.

An angel peeps in awe over the stable wall at the

new born baby Jesus lying in the manger. But the

angel is all that survives. But perhaps the most

fascinating glass here is that reset in the south

windows of the sanctuary. This is a part of

Suffolk with plenty of surviving medieval glass,

so you might at first not give these fragments a

second look. But they are worth careful study

because among them are several birds holding

banners reading 'Jesu Mercy' and 'Jesu Help'.

These must come right at the end of the medieval

period, when liturgical devotion begins to be

expressed in English rather than Latin. You often

come across devotional inscriptions in English at

the end of the late Medieval period on brasses,

screens and the like, but on glass the only other

ones in East Anglia that I can think of are at

Leverington in Cambridgeshire. But those are not

prayer clauses, and far as I know these prayer

clauses written in medieval English are unique

survivals in English glass.

There

are a couple of interesting memorials. The best

is to Charles and Elizabeth Battely, who died in

the early 18th Century, and their memorial is a

vast stone drape behind a tomb which looks rather

alarmingly as if it might be made out of corned

beef. The inscription mentions that it was placed

their by their daughter Jane Merest, hastening to

add that Jane's husband James had been Clerk

Assistant of the House of Lords.

The

church seems to be open every day from Easter to

September, with a keyholder at other times. On

one occasion I tipped up here on a Saturday in

early Spring only to find all three keyholders

out. Heading back to the church to photograph the

outside, I met an old local in the churchyard who

asked me if I wanted to see inside. I explained

that I'd already tried the keyholders, to which

he replied 'don't you worry about that', and gave me another address to

try (something along the lines of "I think

it's the third house along, or possibly the

fourth, just bang on the door, open it and shout

for Val, if she's not in the key's in the kitchen

drawer" or something) but being metropolitan

and not used to such country ways, I demured.

Great

Whelnetham was home to one of the last abuses of

pluralism in Suffolk in the 19th Century. In

1816, during the last years of the lengthy reign

of King George III, a young man called Henry

George Phillips was installed as the Rector here,

for which he would earn £375 a year. Two years

later, he was further installed as the Rector of

the vast parish of Mildenhall, a poor industrial

town 20 miles off, and Suffolk's biggest parish.

His Mildenhall rectorship brought him a further

£450 a year, the combined total of £825 being

worth about £160,000 annually in today's money.

Not unnaturally he preferred to live at Great

Whelnetham, and he employed poorly paid curates

to carry out the liturgical, pastoral and

administrative work at Mildenhall. He started

with some energy - the construction of the north

transept here at Whelnetham was under his

rectorship - but as the years passed he seems to

have preferred the life of a country gentleman.

| Over the next few decades,

the rise of the Oxford Movement would

transform the Church of England and do

away with such abuses, but at the time of

the 1851 Census of Religious Worship the

Reverend Phillips was still firmly

ensconced in both parishes, which appear

to have been equally moribund. Of the

4750 people of Mildenhall only 340

attended morning service there under the

eye of Samuel Banks, curate. At Great

Whelnetham, with its population of 550,

there were 56 people at morning service.

The average in Suffolk was about a

quarter, and sometimes as much as a third

of the population of each parish, the

high water mark of attendances in the

Church of England, but the people of

Mildenhall and Great Whelnetham seemed to

have preferred non-conformism and simple

absence in equal measure. Phillips

appears to have at least been aware that

this didn't look good - compiling the

return for Great Whelnetham, he added the

note that a heavy storm of rain

occured at the time of service which had

reduced the attendance, and in any

case a large proportion of the parish

reside in the hamlet of Sicklesmere and

frequent adjoining churches of parishes

to which they belong. Samuel Banks,

compiling the entry for Mildenhall,

preferred to keep his silence, no doubt

hoping that the figures would speak for

themselves. Remarkably, Phillips hung on

for another 17 years, dying in harness in

1868. There's a memorial tablet to him in

the sanctuary. The pleasing state of the

church today is down to his successors.

|

|

|

|

|

|