| |

|

Hessett is a

fairly ordinary kind of village to the east of Bury St

Edmunds, but its church is one of the most important in

East Anglia for a number of reasons, which I think will

become obvious. Consider for one moment, if you will, the

extent to which the beliefs and practices of a religious

community affect the architecture of its buildings. Think

of a mosque, for instance. Often square, expressing the

democracy of Islam, but without any imagery of the human

figure, for such things are proscribed. Think of a

synagogue, focused towards the Holy Scriptures in the

Ark, but designed to enable the proclaiming of the Word,

and the way that early non-conformist chapels echo this

architecture of Judaism - indeed, those who built the

first free churches, like Ipswich's Unitarian Chapel,

actually called them synagogues.

The shape of a church, then, is no accident. A typical

Suffolk perpendicular church of the 15th century has wide

aisles, to enable liturgical processions, a chancel for

the celebration of Mass, places for other altars, niches

for devotional statues, a focus towards the Blessed

Sacrament in the east, a roof of angels to proclaim a

hymn of praise, a large nave for devotional and social

activities, and wall paintings of the Gospels and

hagiographies of Saints, of the catechism and teachings

of the Catholic Church. As Le Corbusier might have said

if he'd been around at the time, a medieval church is a

machine for making Catholicism happen.

No longer, of course. The radical and violent fracture in

popular religion in the middle years of the 16th century

gave birth to the Church of England, and the new church

inherited buildings that were quite unsuitable for the

new congregational protestant theology, a problem that

the Church of England has never entirely solved.

Over the centuries, the problem has been addressed in

different ways. The early reformers celebrated communion

at a table in the nave, for example, and blocked off the

chancel for other uses. Although this was challenged by

the Laudian party in the early part of the 17th century,

it was the way that many parishes reinvented their

buildings, and most were to stay like that until the

middle years of the 19th century. Some went further. A

pulpit placed halfway down the nave, or even at the back

of the church, meant that the seating could be arranged

so that it no longer focused towards the east, thus

breaking the link with Catholic (and Laudian)

sacramentalism. For several centuries, Anglican churches

focused on the pulpit rather than the altar.

With the coming to influence of the 19th century Oxford

Movement, all this underwent another dramatic change,

with the great majority of our medieval parish churches

having their interiors restored to their medieval

integrity, reinventing themselves as sacramental spaces.

This is the condition in which we find most of them

today, and some Anglican theologians are asking the

question that the Catholic Church asked itself at Vatican

II in the 1960s - is a 19th century liturgical space

really appropriate for the Church of the 21st century?

So, let us hasten at once to Hessett. The church sits

like a glowing jewel in its wide churchyard, right on the

main road through the village. It is pretty well perfect

if you are looking for a fine Suffolk exterior. An

extensive 15th century rebuilding enwraps the earlier

tower, which was crowned by the donor of the rebuilding,

John Bacon.The nave and aisles are deliciously decorated,

reminding one rather of the church at neighbouring

Rougham, although this is a smaller church, and the

aisles make it almost square. A dedicatory inscription on

the two storey vestry in the north east corner bids us

pray for the souls of John and Katherine Hoo, who donated

the chancel and paid for the trimmings to the aisles.

Their inscription has been damaged by protestant

reformers, who obviously did not believe in the efficacy

of prayers for the dead.

Although not comparable with that at Woolpit, the dressed

stone porch is a grand affair, and a bold statement. You

may find the south door locked, but if this is the case

then the priest's door into the chancel is usually open.

And in a way it is a good church to enter via the

chancel, because in this way St Ethelbert unfolds its

treasures slowly.You step into relative darkness - or, at

least, it seems so in comparison with the nave beyond the

rood screen. This is partly a result of the abundance of

dark wood, and in truth the chancel seems rather

overcrowded. The most striking objects in view are the

return stalls, which fill the two westerly corners of the

chancel. These are in the style of a college or school of

priests, with their backs to the rood screen, but then

'returning' around the walls to the east. They are fine,

and are certainly 15th or 16th century. But one of the

stalls, that to the north, is different to the others,

and seems slightly out of place. It is elaborately carved

with faces, birds and foliage. Mortlock thought that it

might have been intended for a private house. The stall

in front of it has heads on it that appear to be wearing

18th century wigs. The sanctuary is largely

Victorianised, with the east window by William Warrington

depicting saints. The south windows of the chancel depict

sumptuous scenes of the Adoration of the Shepherds and

Magi by the O'Connors. The memorial to Lionel Bacon, who

died in 1651, seems extraordinarily ornate for its date.

Is it possible that it was actually erected after the

Restoration, perhaps in the 1660s?

The chancel is

separated from the nave by the 15th century rood screen,

which is elegantly painted and gilt on the west side with

friezes of birds, the beautifully tracery intricately

carved above. The rood screen has been fitted with

attractive iron gates, presumably evidence of

Anglo-catholic enthusiasm here in the early 20th century,

and you step down through them into the light.

A first impression is

that you are entering a much older space than the one you

have left. There is an 18th century mustiness, enhanced

by the box pews that line the aisles. And, beyond, on

walls and in windows, are wonderful things.

The number of surviving wall paintings in England is a

tiny fraction of those which existed before the 15th and

16th centuries. All churches had them, and in profusion.

It isn't enough to say that they were a 'teaching aid' of

a church of illiterate peasants. In the main, they were

devotional, and that is why they were destroyed. However,

it is more complicated than that. Research in recent

years has indicated that many wall paintings were

destroyed before the Reformation, perhaps a century

before. In some churches, they have been punched through

with Perpendicular windows, which are clearly

pre-Reformation. In the decades after the Black Death,

there seems to have been a sea change in the liturgical

use of these buildings, a move away from an

individualistic, devotional usage to a corporate

liturgical one. There is a change of emphasis towards

more education and exegesis. This is the time that

pulpits and benches appear, long before protestantism was

on the agenda. What seems to happen is that many

buildings were intended now to be full of light, and

devotional wall paintings were either whitewashed, or

replaced with catechetical ones.

The decoration of the nave was the responsibility of the

people of the parish, not of the Priest. The wall

paintings of England can be divided into roughly three

groups. Roughly speaking, the development of wall

paintings over the later medieval period is in terms of

these three overlapping emphases.

Firstly, the hagiographies - stories of the Saints. These

might have had a local devotion, although some saints

were popular over a wide area, and most churches seem to

have supported a devotion to St Christopher right up

until the Reformation.

Secondly came those which illustrate incidents in the

life of Christ and his mother, the Blessed Virgin.

Although partly pedagogical, they were also enabling

tools, since private devotions often involved a

contemplation upon them, and at Mass the larger part of

those present would have been involved in private

devotions. These scriptural stories were as likely to

have been derived from apocryphal texts like the Gospel

of Pseudo-Matthew as from the actual Gospels themselves.

Lastly, there are catechetical wall paintings,

illustrating the teachings of the Catholic church. It

should not be assumed that these are dogmatic. Many are

simply artistic representations of stories, and others

are simplifications of theological ideas, as with the

seven deadly sins and the seven cardinal virtues. Some

warn against occasions of sin (gossiping, for example)

and generally wall paintings provided a local site for

discussion and exemplification.

To an extent, all the above is largely true of stained

glass, as well, with the caveat that stained glass was

more expensive, relied on local patronage, and often has

this patronage as a subtext, hence the large number of

heraldic devices and images of local worthies. But it was

also devotional, and so it was also destroyed.

So - what survives at Hessett? The wall paintings first.

Starting in the south east corner of the nave, we have

Suffolk's finest representation of St Barbara, presenting

a tower. St Barbara was very popular in medieval times,

because she was invoked against strikes by lightning and

sudden fires. This resulted from her legend, for her

father, on finding her to be a Christian, walled her up

in a tower until she repented. As a result, he was struck

by lightning, and reduced to ashes. She was also the

patron saint of the powerful building trade, and as such

her image graced their guild altars - perhaps that was

the case here.

Above the south door is another figure, often identified

as St Christopher, but I do not think that this can be

the case. St Christopher is found nowhere else in Suffolk

above a south door. The traditional iconography of this

mythical saint is not in place here, and it is hard to

see how this figure could ever have been interpreted as

such. I suspect it is a result of an early account

confusing the two images over the north and south doors,

and the mistake being repeated in later accounts.

In fact, digital enhancement seems to suggest that there

are two figures above the south door, overlapping each

other slightly. The figure on the right is barefoot, that

on the left is wearing a white gown. There appears to be

water under their feet, and so I think this is an image

of the Baptism of Christ. Perhaps it was once part of a

sequence.

The wall painting opposite, above the north door, is St

Christopher. Although it isn't as clear as himself at,

say, nearby Bradfield Combust, he bestrides the river in

the customary manner, staff in hand. The Christ child is

difficult to discern, but you can see the fish in the

water. Also in the water, and rather unusual, are two

figures. They are rendered rather crudely, almost like

gingerbread men. Could they be the donors of the north

aisle, John and Katherine Hoo in person?

Moving along the north

aisle, we come to the set of paintings for which Hessett

is justifiably famous. They are set one above the other

between two windows, at the point where might expect the

now-vanished screen to a chapel to have been. The upper

section was here first. It shows the seven deadly sins

(described wrongly in some text books as a tree of Jesse,

or ancestry of Christ). Two devils look on as, from the

mouth of hell, a great tree sprouts, ending in seven

images. Pride is at the top, and in pairs beneath are

Gluttony and Anger, Vanity and Envy, Avarice and Lust.

Some attempt has been made to erase the image for Lust,

which may simply be mid-16th century puritan prurience on

the part of some reformer here. This would suggest that

this catechetical tool was here right up until the

Reformation. If so, they were unsuccessful, because his

erect penis is still discernible.

The idea of 'Seven Deadly Sins' was anathema to the

reformers, because it is entirely unscriptural. Rather,

as a catechetical tool, it is a way of drawing together a

multitude of sins into a simplistic aide memoire.

This could then be used in confession, taking each of

them one at a time and examining ones conscience

accordingly. It should not be seen simply as a 'warning'

to ignorant peasants, for the evidence is that the

ordinary rural people of late medieval England were

theologically very articulate. Rather, it was a tool for

use, in contemplation and preparation for the sacrament

of reconciliation, which may well have ordinarily taken

place in the chapel here.

The wall painting beneath the Sins is even more

interesting. This is a very rare 'Christ of the Trades',

and dates from the early 15th century, about a hundred

years after the painting above. It is rather faded, and

takes a while to discern, and not all of it is decodable.

However, enough is there to be fascinating. The image of

the 'Christ of the Trades' is known throughout

Christendom, and contemporary versions with this can be

found in other parts of Europe. It shows the risen Christ

in the centre, and around him a vast array of the tools

and symbols of various trades. One theory is that it

depicts activities that should not take place on a

Sunday, a holy day of obligation to refrain from work,

and that these activities are wounding Christ anew.

Perhaps the most fascinating symbol, and the one that

everyone notices, is the playing card. It shows the six

of diamonds. Does it represent the makers of playing

cards? If so, it might suggest a Flemish influence. Or

could it be intended to represent something else?

Whatever, it is one of the earliest representations of a

playing card in England. Why is this here? It may very

well be that there was a trades gild chantry chapel at

the east end of the north aisle, and this painting was at

its entrance.

At the east end of the

north aisle now is the church's set of royal arms.

Cautley saw it in the vestry in the 1930s, and identified

it as a Queen Anne set. Now, with additions stripped

away, it is revealed as a Charles II set from the 1660s,

and a very fine one. It is fascinating to see it at such

close range. Usually, they are set above the south door

now, although they would originally have been placed

above the chancel arch, in full view of the congregation,

a gentle reminder of who was in charge.

And so to the glass, which on its own would be worth

coming to Hessett to see. Few Suffolk churches have such

an expanse, none have such a variety, or glass of such

quality and interest. It consists essentially of two

ranges, the life and Passion of Christ in the north aisle

(although some glass has been reset across the church),

and images and hagiographies of Saints in the south

aisle.

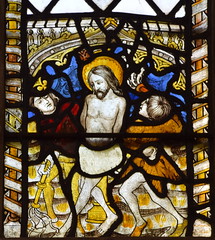

In the north aisle, the scourging of Christ stands out,

the wicked grins of the persecutors contrasting with the

pained nobility of the Christ figure. In the next window,

Christ rises from the dead, coming out of his tomb like

the corpses in the doom paintings at Stanningfield, North

Cove and Wenhaston. The Roman centurion sleeps soundly in

the foreground.

The most famous image

is in the east window of the south aisle. Apparently, it

shows a bishop holding the chain to a bag, with four

children playing at his feet. I say apparently, because

there is rather more going on here than meets the eye.

The reason that this image is so famous is that the small

child in the foreground is holding what appears to be a

golf club or hockey stick, and this would be the earliest

representation of such an object in all Europe. The whole

image has been said to represent St Nicholas, who was a

Bishop, and whose legends include a bag of gold and a

group of children.

Unfortunately, this is not the case. St Nicholas is never

symbolised by a bag of gold, and there are three children

in the St Nicholas legend, not four. In any case, the

hand in the picture is not holding the chain to a bag at

all, but a rosary, and the hockey stick is actually a

fuller's club, used for dyeing clothes, and the symbol of

St James the Less.

What has happened here is that the head of a Bishop has

been grafted on to the body of a figure which is probably

still in its original location. The three lights of this

window contained a set of the Holy Kinship. The light to

the north of the 'Bishop' contains two children playing

with what ae apparently toys, but when you look closely

you can see that one is holding a golden shell, and the

other a poisoned chalice. They are the infant St James

and St John, and the lost figure above them was their

mother, Mary Salome. This means that the figure with the

Bishop's head is actually Mary Cleophas, apocryphal

mother of St Simon, St Jude, St Philip and St James the

Less with his fullers club. The third light to the south,

of course, would have depicted the Blessed Virgin and

child, but she is lost to us.

Not only this, but

Hessett has some very good 19th Century glass which

complements and does not overly intrude. We have already

mentioned the glass by William Warrington and the

O'Connor Brothers in the chancel, and the best is beneath

the tower, the west window with scenes of the Passion in

a fully 15th Century style by Clayton & Bell.

If the windows and wall paintings were all there was,

then Hessett would be remarkable enough. But there is

something else, two things, actually, that elevate it

above all other Suffolk churches, and all the churches of

England. For St Ethelbert is the proud owner of two

unique survivals. At the back of the church is a chest,

no different from those you'll find in many a parish

church. In common with those, it has three separate

locks, the idea being that the Rector and two

Churchwardens would have a key each, and it would be

necessary for all three of them to be present for the

chest to be opened. It was used for storing parish

records and valuables.

At some point, one of the keys was lost. There is an old

story about the iconoclast William Dowsing turning up

here and demanding the chest be opened, but on account of

the missing key it couldn't be. Unfortunately, this story

isn't true, for Dowsing never recorded a visit Hessett.

The chest was eventually opened in the 19th century.

Inside were found two extraordinary pre-Reformation

survivals. These are a pyx cloth and a burse. The pyx

cloth was draped over the wooden canopy that enclosed the

blessed sacrament (one of England's four surviving

medieval pyxes is also in Suffolk, at Dennington) before

it was raised above the high altar. The burse was used to

contain the host before consecration at the Mass. They

are England's only surviving examples, and they're both

here. Or, more precisely they aren't, for both have been

purloined by the British Museum, the kind of theft that

no locked church can prevent.

But there are life-size photos of both either side of the

tower arch. The burse is basically an envelope, and

features the Veronica face of Christ on one side with the

four evangelistic symbols in each corner. On the other is

an Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God. The survival of both is

extraordinary. It is one thing to explore the furnishings

of lost Catholic England, quite another to come face to

face with articles that were actually used in the

liturgy.

In front of the pictures stands the font, a relatively

good one of the early 15th century, though rather less

exciting than everything going on around it. The

dedicatory inscription survives, to a pair of Hoos of an

earlier generation than the ones on the vestry.Turning

east again, the ranks of simple 15th century benches are

all of a piece with their church. They have survived the

violent transitions of the centuries, and have seated

generation after generation of Hessett people. They were

new here when this church was alive with coloured light,

with the hundreds of candles flickering on the rood beam,

the processions, the festivals, and the people's lives

totally integrated with the liturgy of the seasons. For

the people of Catholic England, their religion was as

much a part of them as the air they breathed. They little

knew how soon it would all come to an end.

And so, there it is - one of the most fascinating and

satisfactory of all East Anglia's churches. And yet, not

many people know about it. We are only three miles from

the brown-signed honeypot of Woolpit, where a constant

stream of visitors come and go. I've visited Hessett many

times, and never once encountered another visitor. Still,

there you are, I suppose. Perhaps some places are better

kept secret. But come here if you can, for here is a

medieval worship space with much surviving evidence of

what it was actually meant to be, and meant to do.

Simon

Knott, October 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Churches of East

Anglia websites are

non-profit-making, in fact they

are run at a loss. But if you

enjoy using them and find them

useful, a small contribution

towards the costs of web space,

train fares and the like would be

most gratefully received. You can

donate via Paypal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|