| |

|

In the 1960s, Ipswich went mad.

Town planners foresaw a rise in the town's population

towards half a million people, and so with natural

excitement they decided to cross and encircle the

existing town centre with a network of dual carriageways

lined with office blocks. They didn't get very far with

their plans before the men in white coats came and took

them away, releasing them into the wild somewhere like

Croydon or Wolverhampton, but the towering Civic Centre,

the brutalist police station and the Civic Drive road

system were left as evidence of their ambitions. The

Civic Centre and the police station, both which stood

directly opposite this church, have since been

demolished, but the four lane Civic Drive still cuts

across what was the Mount residential area, the little

terraces all demolished to make way for the 20th century,

and separates St Matthew from the rest of the town

centre.

Today, the Ipswich plan designates this whole area for

residential use, and the modern civil servants have moved

down to the river. This new plan, if it emerges, can only

serve the church well, sitting beside Civic Drive as it

does. The church is perhaps less well-known than the

other working town centre churches. Partly, this is

because it is the only one of them which is kept locked,

but also because it requires an effort to find it and get

across to it if you are a visitor. Because of this, many

people don't realise that the church contains a treasure

of national importance. This is the early 16th Century

font, which is quite unlike any other in Suffolk, and is

perhaps unique in England.This

must once have been quite a small building, but events

over the centuries have enlarged into the church we see

today. The core is 15th Century, including the lower part

of the tower. The 19th Century expansion was substantial,

made necessary by the proximity of the Ipswich Barracks,

for this became the Garrison church. This explains the

size of the aisles which are as wide as the nave, and

were intended to increase capacity as much as to allow

for the revival of processions. The chancel was also

rebuilt, but retained its medieval roof.

Until 1970 the church was hemmed in to the east, but the

construction of Civic Drive opened up this view, which

isn't a particularly good one. This end of the church is

entirely Victorian, and when you look at it you realise

that it was built into existing buildings and wasn't

intended to be seen. Because of this, it comes as a

surprise to find that the west end on Portman Road is by

contrast quite pastoral, a pretty setting for the tower.

Before the destruction of the houses to the east this

would have been the familiar view, the churchyard

stretching away to the south, but this in turn was partly

built over in the 1960s with the construction of the new

roads and of a church school. The part of the graveyard

immediately beyond the chancel on Civic Drive was turned

into a small garden. A footpath runs along the north side

which will bring you through to the main entrance, the

west door under the tower. You step into a broadly

Victorian interior, and find the font in the north aisle.

East Anglia is famous for its Seven Sacrament fonts, 13

of which are in Suffolk. These show the seven sacraments

of the Catholic Church, and are rare survivals. So much

English medieval Catholic iconography was destroyed by

the Protestant reformers of the 16th century, and the

Puritans of the 17th century. Here at St Matthew we find

an even rarer survival of England's Catholic past, a font

whose panels show a sequence of images of events in the

life of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Before describing it, I have to make the point that this

really is one of the dozen most important and significant

medieval art survivals in Suffolk, and one of the finest

late medieval fonts in England. There is nothing as good

as this in the Victorian and Albert Museum, or in the

British Museum. I make this point simply because on every

occasion that I have visited, the person accompanying me

(they don't let you visit the church on your own) did not

seem to realise quite how important the font was, and

gave the impression that the parish, though they care for

it lovingly, also did not realise what a treasure, what a

jewel, they had on the premises. "It's quite

pretty," said the lady when I visited in September

2016. The leaflet in the church describes it as 14th

Century, which the nice lady took as holy writ and didn't

really believe me when I suggested that it wasn't.

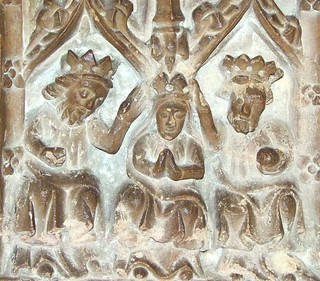

In fact, it was made during the second decade of the 16th

Century. Of the eight

panels, one has a Tudor rose and another a foliage

pattern, but five of them depict events in the devotional

story of Mary, mother of Jesus. These five reliefs, and a

sixth of the Baptism of Christ, are amazing art objects.

They show the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin with

Gabriel unfurling a banner from which a dove emerges to

whisper in Mary's ear; The Adoration of the Magi, with

the wise men pulling a blanket away from the Blessed

Virgin and child as if to symbolise their revelation to

the world; the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, with

Mary radiating glory in a mandala, which four angels use

to convey her up to heaven in bodily form; the Coronation

of the Queen of Heaven, the crowned figures of God the

Father and God the Son placing a crown on the Blessed

Virgin's head while the Dove of the Holy Spirit races

down directly above her; and the Mother of God Enthroned, the crowned figure of the Blessed

Virgin sitting on the left of and looking at (and thus

paying homage to) her crowned son on the right, who is

holding an orb.

The late Dr John Blatchly thought

that this last panel of the Mother of God enthroned was

intended as a representation of Catherine of Aragon and

her husband Henry VIII. The evidence for this is

circumstantial, but there is no doubt that this font is

an artifact of the ongoing early 16th Century drama which

would eventually result in the English Reformation. John

Blatchly's research showed that this font was paid for

and installed by the rector of St Matthew, one John

Bailey, to celebrate the Miracle of the Maid of Ipswich,

which occured in this very parish in 1516 and was held in

renown all over England in the few short years left

before the Reformation intervened. The popularity of the

Miracle, in which Joan, a young Ipswich girl, has a

near-death encounter and experiences visions of the

Virgin Mary, was widely used by the Catholic Church as a

buttress against the murmurings of reformers.

In their book The Miracles of

Lady Lane, John Blatchly and Diarmaid MacCulloch

give a fascinating and often convoluted account of the

battles between Bailey and a much more significant local

figure, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Ipswich was Wolsey's

power base, and he attempted to consolidate his power by

taking control of the Shrine of Our Lady of Grace of

Ipswich which just happened to be in the parish of St

Matthew, a hundred yards or so to the east of this

church. The shrine was one of the most popular pilgrimage

sites in England. Bailey's celebration of the Miracle was

partly a way of competing with Wolsey for fame and

influence in the town, but also of increasing his own

hold on control of the Shrine. Those who visited the

shrine would also come to St Matthew and tell their bedes

around the panels of the font. The devotion to Our Lady

of Grace and the celebration of the Miracle of the Maid

of Ipswich would become intertwined. Church and shrine

would become inseparable parts of the same pilgrim

experience. Between 1517 and 1522, both Henry VIII and

Catherine of Aragon made journeys to the shrine, set

beside the Westgate in the parish of St Matthew. They

probably visited the church as well. Other visitors

included the the future saint Thomas More, and of course

Wolsey himself. But in 1525 Bailey died and left the way

open for the Cardinal, who in his turn would completely

over-reach himself and fall in his own way just five

years later. Henry's divorce from Catherine would entail

a break with Rome and over the next thirty years the

birth of a new Church of England. It is the kind of thing

Trollope would have written about if he had been around

in the 16th Century.

Blatchly and MacCulloch's book is

memorable as a picture of the incredible religious

fervour in Ipswich in the early years of the 16th

Century, a tale of near-hysterical enthusiasms that would

spill over into passion and violence. Blatchly notes that

the sequence of at least some of the Marian images on the

font was replicated by a sequence of inns down the mile

of Ipswich's main street, now the line of Carr Street,

Tavern Street and Westgate Street, which led to the

shrine. One of the inns, the Salutation (ie,

Annunciation) at the start of Carr Street survives in

business under the same name to this day. But in time of

course Ipswich would become well-known as the most

puritan of towns in the most puritan of England's

regions.

Remarkably, two of the four figures

around the base are probably intended as Joan, the Maid

of Ipswich, and John Bailey the Rector himself.

Most guide books describe the

panels of the font as the five Joyful Mysteries of the

Rosary. In fact, this is technically not the case,

although certainly the font was intended for use in

rosary meditations. We know that the rosary was a hugely

popular devotion in medieval England, and that a persons

'bedes' were their most valued possession. They played a

major part in personal devotion, but were also important

as a way of participating in the liturgy, and as an

expression of communal piety. Many pre-Reformation

memorials show people holding their rosary beads.

However, what we now think of as the Rosary sequence only

dates from the 14th century or so, and was one among

several in common usage. Praying with the rosary had been

greatly popularised in England by St Thomas of Canterbury

in the 12th century, who devised a series of seven joyful

mysteries, including the Adoration of the Magi and the

Assumption of the Blessed Virgin. Most sequences were of

five meditations. In time, the Joyful Mysteries would

come to be Mary's earthly experiences, and the Glorious

Mysteries her heavenly ones.

Because personal devotion was considered a diversion from

congregational worship, and Marian devotion was thought

superstitious, the rosary was completely anathematised by

the 16th century Protestant reformers, and attempts were

made to write it out of history by destroying images of

it on brasses and memorials. Within forty years of this

font being produced, use of rosary beads was a criminal

act in England.

The survival of an image of the Assumption is

particularly interesting. We still have much surviving

evidence of religious life in England before the Church

of England came along, but it does not really reveal to

us the relative significance of different devotions,

simply because some of the major cults and their images

were ruthlessly rooted out and destroyed. The Assumption

is a case in point. 15th and early 16th Century wills and

bequests reveal a great devotion to the Blessed Virgin,

particularly to the feast of the Assumption, which is

celebrated on August 15th.

This is at the height of the harvest, of course, and it

is not difficult to see the connection between this feast

and the culmination of the farming year, or the

importance to farmworkers of a festival at this time.

More than 200 Suffolk parish churches were dedicated to

the Assumption. When the dedications of Anglican churches

were restored in the 19th century after several centuries

of disuse these generally became 'St Mary', although some

have been restored correctly since, at Haughley and

Ufford for example. The Church of England, of course,

does not recognise the doctrine of the Assumption.

Of equal significance are the other images, all

remarkable survivals. And why the Baptism of Christ? In

fact, this is the most common 'odd panel out' on the

Seven Sacrament fonts, and reminds us of the significance

of baptism in the medieval church. It was the sacrament

by which infants received their mystical commission to

the Christian life and to the daily life of the parish,

and was by total immersion, hence the size of medieval

font bowls.

Within thirty years of this font

being installed here, injunctions against images

proscribed its panels. Most likely it was plastered over,

for the parish would still need a font. The bowl still

shows traces of plaster today.

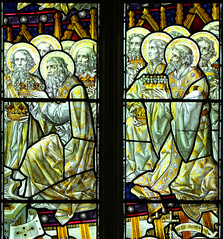

The font is not quite the only

medieval survival here, for the north aisle also retains

panels from the rood screen, built into a 19th century

screen. You might miss these, because ordinarily chairs

are stacked against them. Three of the panels show

bishops, and the other two show cheering crowds of seven

and nine people respectively. I do not think that these

can be in their original configuration. Roy Tricker

thought that the crowds were portraits of parishioners,

which may be so, in which case these may besurviving

panels of the screen to the chantry altar of the guild of

Erasmus, which was established here.

There is clear evidence of the location of at least one

nave altar, since a squint kicks in from the north aisle.

There are two good 17th century wall memorials in the

chancel, the best being to Anthony Penning and his wife

depicting their children weeping, some holding skulls to

show that they pre-deceased their parents.

| Much of the 19th century

woodwork is from the workshops of two major 19th

century Ipswich carpenters, Henry Ringham and

John Corder. Ringham's work can be found in

several Suffolk churches, most notably St Mary le

Tower, Woolpit and Great Bealings, while Corder

was an architect responsible for several

restorations, including Swilland. Both have

Ipswich roads named after them. The church has an extensive

collection of late 19th and early 20th Century

glass, not all of it good, but happily by a wide

variety of workshops. The great curiosity is the

window in the east end of the south aisle, which

depicts Jane Trimmer Gaye, wife of a 19th Century

rector, flanked by female members of her

husband's flock with images of birth and

death. It was designed by her brother Frank

Howard, and made by George Hedgeland. Another

oddity is Percy Bacon's Christ flanked by St

Edmund and St Felix - for the last hundred years

the Saints have stood here with their names

transposed.

There is a frankly functional modern screen, with

a curious Anglo-catholic style rood which looks

most out of place, for St Matthew today is very

much in the evangelical tradition. But the lady

who allowed me entry told me that people liked

it, so I expect nobody minds too much.

|

|

|

Simon

Knott, August 2020

|

|

|