| |

|

|

|

There are ages of faith

which leave their traces in splendour and beauty,

as acts of piety and memory. East Anglia is full

of silent witnesses to tides which have ebbed and

flowed. Receding, they leave us in their wake

great works from the passing ages, little Norman

churches which seem to speak a language we can no

longer understand but which haunts us still, the

decorated beauty of the 14th Century at odds with

the horrors of its pestilence and loss, the

perpendicular triumph of the 15th Century church

before its near-destruction in the subsequent

Reformation and Commonwealth, the protestant

flowering of chapels and meeting houses in almost

all rural communities, and most obvious of all

for us today the triumphalism of the Victorian

revival.

But even as tides recede, piety and memory

survive, most often in quiet acts and intimate

details. The catholic church of Holy Family and

St Michael at Kesgrave is one of their great 20th

Century treasure houses. |

At the time of the 1851 census of

religious worship, Kesgrave was home to just 86 people,

79 of whom attended morning service that day, giving this

parish the highest percentage attendance of any in

Suffolk. However, they met half a mile up the road at the

Anglican parish church of All Saints, and the current

site of Holy Family was then far out in the fields. In

any case, it is unlikely that any of the non-attenders

was a Catholic. Today, Kesgrave is a sprawling eastern

suburb of Ipswich, home to about 10,000 people. It

extends along the A12 corridor all the way to Martlesham,

which in turn will take you pretty much all the way to

Woodbridge without seeing much more than a field or two

between the houses.

Holy Family was erected in the 1930s, and serves as a

chapel of ease within the parish of Ipswich St Mary.

However, it is still in private ownership, the

responsibility of the Rope family, who, along with the

Jolly family into which they married, owned much of the

land in Kesgrave that was later built on.

The growth of Kesgrave has been so rapid and so extensive

in these last forty years that radical expansions were

required at both this church and at All Saints, as well

as to the next parish church along in the suburbs at

Rushmere St Andrew. All of these projects are

interesting, although externally Holy Family is less

dramatic than its neighbours. It sits neatly in its trim

little churchyard, red-brick and towerless, a harmonious

little building if rather a curious shape, of which more

in a moment. Beside it, the underpass and roundabout

gives it a decidedly urban air. But this is a church of

outstanding interest, as we shall see.

It was good to come back to Kesgrave. As a member of St

Mary's parish I generally attended mass at the parish's

other church, a couple of miles into town, but I had been

here a number of times over the years, either to mass or

just to wander around and sit for a while. These days,

you generally approach the church from around the back,

where you'll find a sprawling car park typical of a

modern Catholic church. To the west of the church are

Lucy House and Philip House, newly built for the work of

the Rope family charities. Between the car park and the

church there there is a tiny, formal graveyard, with

crosses remembering members of the Rope and Jolly

families.

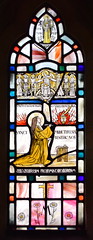

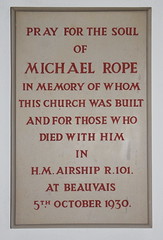

Access to the church is usually through a west door these

days, but if you are fortunate enough to enter through

the original porch on the north side you will have a

foretaste of what is to come, for to left and right are

stunning jewel-like and detailed windows depicting St

Margaret and St Theresa on one side and St Catherine and

the Immaculate Conception on the other. Beside them, a

plaque reveals that the church was built to the memory of

Michael Rope, who was killed in the R101 airship disaster

of 1930.

Blue Peter-watching boys like me,

growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, were enthralled by

airships. They were one of those exciting inventions of a

not-so-distant past which were, in a real sense,

futuristic, a part of the 1930s modernist project that

imagined and predicted the way we live now. And they were

just so big. But they were doomed, because the

hydrogen which gave them their buoyancy was explosive.

As a child, I was fascinated by the R101 airship and its

disaster, especially because of that familiar photograph

of its wrecked and burnt-out fuselage sprawled in the

woods on a northern French hillside. It is still a

haunting photograph today. The crash of the R101 put an

end to airship development in the UK for more than half a

century.

Of course, this is all ancient history now, but in the

year 2001 I had the excellent fortune to be shown around

Holy Family by Michael Rope's widow, Mrs Lucy Doreen

Rope, née Jolly, who was still alive, and then in her

nineties. She was responsible for the building of this

church as a memorial to her husband. We paused in the

porch so that I could admire the windows. "Do you

like them?" Mrs Rope asked me. "Of course, my

sister-in-law made them."

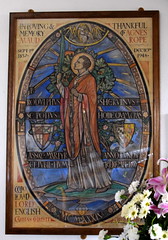

Her sister-in-law, of course, was Margaret Agnes Rope,

who in the first half of the twentieth century was one of

the finest of the Arts and Craft Movement stained glass

designers. She studied at Birmingham, and then worked at

the Glass House in Fulham with her cousin, Margaret Edith

Aldrich Rope, whose work is also here. But their work can

be found in churches and cathedrals all over the world.

What Mrs Rope did not tell me, and what I found out

later, is that these two windows in the porch were made

for her and her husband Michael as a wedding present.

Doreen Jolly and Michael Rope were married in 1929.

Within a year, he was dead. Mrs Rope was just 23 years

old.

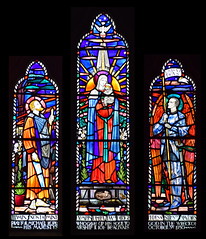

The original church from the 1930s is the part that you

step into, beneath a tympanum by Ellen Mary Rope, Michael

Rope's aunt, made in the last years of her life. It

depicts the Blessed Virgin cradling a lamb between the

young Christ and St John the Baptist and the inscription Ecce

Agnus Dei, 'behold the Lamb of God'.. You enter to

the bizarre sight of a model of the R101 airship

suspended from the roof. The nave altar and tabernacle

ahead are in the original sanctuary, and you are facing

the liturgical east (actually south) of the original

building, and what an intimate space this must have been

before the church was extended. Red brick outlines the

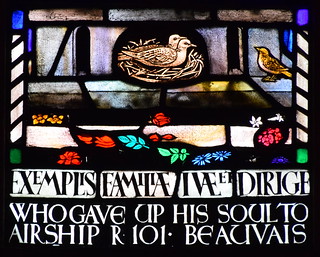

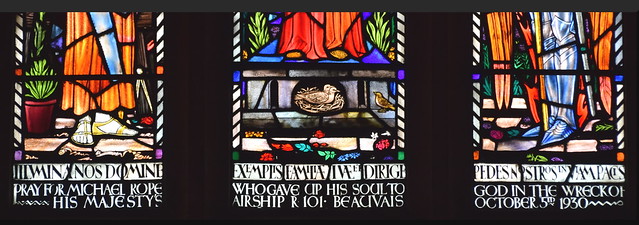

entrance to the sanctuary, and here are the three windows

made by Margaret Rope for the original church. The first

is the three-light sanctuary window, depicting the

Blessed Virgin and child flanked by St Joseph and St

Michael. Two doves sit on a nest beneath Mary's feet,

while a quizzical sparrow looks on. St Michael has the

face of Michael Rope. The inscription beneath reads Pray

for Michael Rope who gave up his soul to God in the wreck

of His Majesty's Airship R101, Beauvais, October 5th

1930.

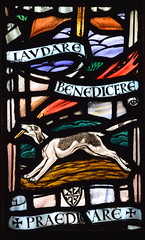

Next, a lancet in the right-hand

side of the sanctuary contains glass depicting St

Dominic. A dog runs with a burning brand beneath his feet

through the inscription Laudare, Benedicere,

Praedicare, ('to praise, to bless, to preach'). The

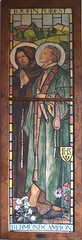

third window is in the west wall of the church (in its

day, the right hand side of the nave), depicting St

Thomas More and St John Fisher, although at the time the

window was made they had not yet been canonised. The

inscription beneath records that the window was the gift

of a local couple in thankfulness for their

conversion to the faith for which the Blessed Martyrs

Thomas More and John Fisher gave their lives. A rose

bush springs from in front of the martyrs' feet.

By the 1950s, Holy Family was no

longer large enough for the community it served, and it

was greatly expanded to the east to the designs of the

architect Henry Munro Cautley. Cautley was a bluff

Anglican of the old school, the retired former diocesan

architect of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich, but he would

have enjoyed designing a church for such an intimate

faith community, and in fact it was his last major

project before he died in 1959. The original sanctuary

was retained as a blessed sacrament chapel, and the

church was turned ninety degrees to face east for the

first time. The north and south sides of the new church

received three-light Tudor windows in the style most

beloved by Cautley, as seen also at his Ipswich County

Library in Northgate Street, and the former Fosters (now

Lloyds) Bank in central Cambridge.

Although the Rope family had farmed at Blaxhall near

Wickham Market for generations, Margaret Rope herself was

not from Suffolk at all, and nor was she at first a

Catholic. She was born in Shrewsbury in 1882, the

daughter of Henry Rope, a surgeon at Shrewsbury

Infirmary, and a son of the Blaxhall Rope family. The

largest collection of Margaret Rope's glass is in

Shrewsbury Cathedral. When Margaret was 17, her father

died. The family were received into the Catholic church

shortly afterwards. A plaque was placed in the entrance

to Shrewsbury Infirmary to remember her father. When the

hospital was demolished in the 1990s, the plaque was

moved to here, and now sits in the north aisle of the

1950s church. In her early days in London Margaret Rope

designed and made the large east window at Blaxhall

church as a memorial to her grandparents. It features her

younger brother Michael, and is believed to be the only

window that she ever signed.

In her early forties, Margaret Rope took holy orders and

entered the Carmelite Convent at nearby Woodbridge, but

continued to produce her stained glass work until the

community moved to Quidenham in Norfolk, when poor health

and the distances involved proved insurmountable. She

died there in 1953, and so she never saw the expanded

church. Her cartoons, the designs for her windows, are

placed on the walls around Holy Family. Some are for

windows in churches in Scotland and Wales, one for a

window in the English College in Rome. Among them are the

roundels for within the enclosure of Tyburn Convent in

London. "They had to remove the windows there during

the War", said Mrs Rope. "Of course, with me,

you have to ask which war!"

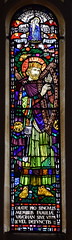

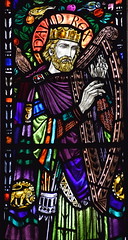

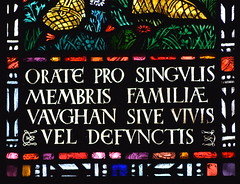

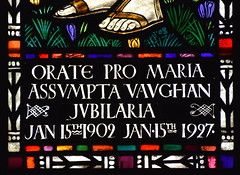

Turning to the east, we see the new

sanctuary with its high altar, completed in 1993 as part

of a further reordering and expansion, which gave a large

galilee porch, kitchen and toilets to the north side of

the church. The window above the new sanctuary has three

lights, and the two outer windows were made by Margaret

Rope for the chapel of East Bergholt convent to the south

of Ipswich. They remember the Vaughan family, into which

Margaret Rope's sister had married, and in particular one

member, a sister in the convent, to celebrate her 25 year

jubilee. The convent later became Old Hall, a famous

commune. The panels depict the prophet Isaiah and King

David.

The central light between them is controversial. Produced

in the 1990s and depicting the risen Christ, it really

isn't very good, and provides the one jarring note in the

church. It is rather unfortunate that it is in such a

prominent position. It is not just the quality of the

design that is the problem. It lets in too much light in

comparison with the two flanking lights. "The glass

in my sister-in-law's windows is half an inch

thick", Mrs Rope told me. "In the workshop at

Fulham they had a man who came in specially to cut it for

them". The glass in the modern light is simply too

thin.

Despite the 1990s extension, and as

so often in modern urban Catholic churches, Holy Family

is already not really big enough, although it is hard to

see that there could ever be another expansion. We walked

along Munro Cautley's south aisle, and at that time the

stations of the cross were simple wooden crosses.

However, about three months after my conversation with

Mrs Rope, the World Trade Centre in New York was attacked

and destroyed, and among the three thousand people killed

were two local Kesgrave brothers who were commemorated

with a new set of stations in cast metal.

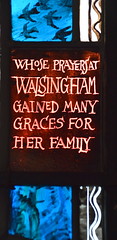

Here also is a 1956 memorial window by Margaret Rope's

cousin, Margaret Edith Aldrich Rope, to Mrs Rope's mother

Alice Jolly, depicting the remains of the shrine at

Walsingham and the Jolly family at prayer before it.

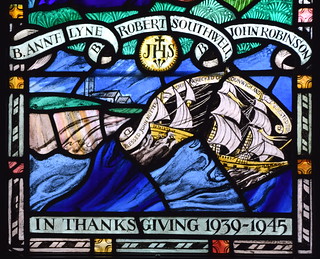

Another MEA Rope window is across the church in the

galilee, a Second World War memorial window, originally

on the east side of the first church before Cautley's

extension. It depicts three of the English Martyrs,

Blessed Anne Lynne, Blessed Robert Southwell and Blessed

John Robinson, as well as the shipwreck of Blessed John

Nutter off of Dunwich, with All Saints church on the

cliffs above.

The galilee is designed for

families with young children to play a full part in mass,

and is separated from the church by a glass screen. At

the top of the screen is a small panel by Margaret Rope

which is of particular interest because it depicts her

and her family participating in the Easter vigil,

presumably in Shrewsbury Cathedral. This is hard to

photograph because it is on an internal window between

two rooms.

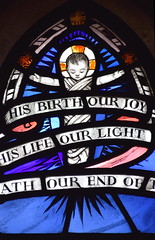

A recent addition to the Margaret Edith Aldrich Rope

windows here is directly opposite, newly installed on the

south side of the nave. It was donated by her

great-nephew. It depicts a nativity scene, the Holy

Family in the stable at Bethlehem, an angel appearing to

shepherds on the snowy hills beyond. It is perhaps her

loveliest window in the church.

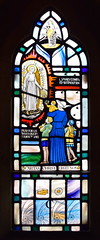

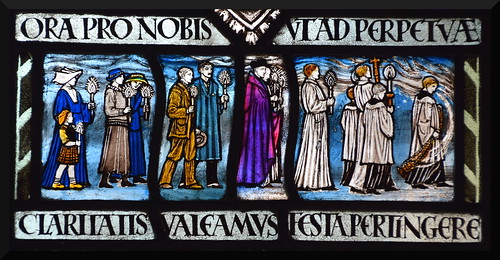

Finally, back across the church.

Here, beside the brass memorial to Henry Rope, is a

window depicting the Blessed Virgin and child, members of

the Rope family in the Candlemas procession beneath. The

inscription reminds us to pray for the soul of Sister

Margaret of the Mother of God, mistress of novices and

stained glass artist, Monastery of the Magnificat of the

Mother of God, Quidenham, Norfolk, entered Carmel 14th

September 1923, died 6th December 1953. Sister

Margaret of the Mother of God was, of course, Margaret

Rope herself. She was buried in the convent at Quidenham,

a Shrewsbury exile at rest in the East Anglian soil of

her forebears.

Margaret Rope had made the main

body of this window herself, as a present for her mother.

After passing into the hands of her sister, the window

was then used as her memorial, the outer panels with the

inscription added by her cousin Margaret Edith Aldrich

Rope. Intriguingly, Margaret Rope's great-nephew Arthur

Rope has suggested to me that her cousin also replaced

the small kneeling figure panel bottom right, which in

Margaret Rope's cartoon for the window depicts a

self-caricature. As he points out, the figure there now

looks very much like the nun kneeling on Margaret Edith

Aldrich Rope's later memorial to Alice Jolly across the

church.

Back in 2001, we were talking about

the changing Church, and I asked Mrs Rope what she

thought about the recently introduced practice of

transferring Holy Days on to the nearest Sunday, so that

the teaching of them was not lost. Mrs Rope approved, a

lady clearly not stuck in the past. She had a passion for

ensuring that the Faith could be shared with children. As

we have seen, her church is designed so that young

families can take a full part in the Mass. But she was

sympathetic to the distractions of the modern age.

"The world is so exciting for children these

days", she said. "I think it must be difficult

to bring them up with a sense of the presence of

God." She smiled. "Mind you, my son is 70 now!

And I do admire young girls today. They have such

spirit!"

And so this grand old lady left me

to potter about in her wonderful treasure house. As I did

so, I thought of medieval churches I have visited, which

were similarly donated by the Mrs Ropes of their day,

perhaps even for husbands who had died young. They not

only sought to memorialise their loved ones, but to

consecrate a space for prayer, that masses might be said

for the souls of the dead. This was the Catholic way, a

Christian duty. Before the Reformation, this was true in

every parish in England. It remained true here at

Kesgrave.

One of the great losses to

the Church of England is the practice of praying

for the souls of the dead, anathematised at the

Reformation, and now encouraged in only a few

Anglican parishes. Prayers for our lost loved

ones bound our communities together, the past

with the present, the living and the dead. Today,

all over the land, many Anglican congregations

are shrinking, and yet on the soft ground around

their churches the locals enact a pagan cult of

the dead, worshipping their recent ancestors with

propitiatory flowers, often unable to combine

this act with a prayer said inside a sacred

building, increasingly unaware that such a thing

might even be appropriate. It seems a shame.

And so, finally, back outside to the small

graveyard of Holy Family. Simple crosses line the

low yew hedging, as if this were a convent

cemetery. Side by side are two particular

crosses. One remembers Margaret Edith Aldrich

Rope, artist, 1891-1988. The other remembers Lucy

Doreen Rope, founder of this church, 1907-2003. |

|

|

Simon

Knott, April 2018

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|

|