| |

|

I always look forward to coming back to

Kettlebaston. It is likely that anyone who knows the

churches of Suffolk well will have Kettlebaston among

their favourites. The setting is delectable, in the

remote Suffolk hills between Hadleigh and Stowmarket. The

building is at once elegant and interesting, the interior

memorable, but most fascinating of all perhaps is the

story behind the way it is today.

In 1963, in the thirty-third year of his incumbency as

Rector of the parish of Kettlebaston, Father Harold Clear

Butler sent a letter to a friend. "You are

right,"he wrote. "There is no congregation any

more." In failing health, he relied on the family of

a vicar who had retired nearby to carry out the

ceremonies of Easter week that year. In 1964, Father

Butler himself retired, and an extraordinary episode in

the history of the Anglo-Catholic movement in Suffolk

came to an end.

There may have been no congregation, but St Mary at

Kettlebaston was a shrine, to which people made

pilgrimages from all over England. Here was the

liturgically highest of all Suffolk's Anglican churches,

where Father Butler said the Roman Mass every day,

celebrated High Mass and Benediction on Sunday, dispensed

with churchwardens, flouted the authority of the Anglican

diocese by tearing down state notices put up in the

porch, refused to keep registers, and even, as an

extreme, ignored the office of the local Archdeacon of

Sudbury. An entry from the otherwise empty registers for

October 2nd 1933 reads Visitation of Archdeacon of

Sudbury. Abortive. Archdeacon, finding no churchwardens

present, rode off on his High Horse!

Father Butler came to this parish when the Anglo-Catholic

movement was at its height, and survived into a poorly

old age as it retreated, leaving him high and dry. But

not for one moment did he ever compromise.

Kettlebaston church is not just remote liturgically. You

set off from the vicinity of Hadleigh, finding your way

to the back of beyond at Brent Eleigh - and then beyond

the back of beyond, up the winding roads that climb into

the hills above Preston. Somewhere here, two narrow lanes

head north. One will take you to Thorpe Morieux, and one

to Kettlebaston, but I can never be sure which is which,

or even if they are always in the same place. Finding

your way to this, one of the most remote of all Suffolk

villages, can be like finding your way into Narnia. Once

in the village, you find the church surrounded by a high

yew hedge, through which a passage conducts a path into

the graveyard. On a buttress, a statue of the Coronation

of the Queen of Heaven sits behind a grill. It is a copy

of an alabaster found under the floorboards during the

1860s restoration. The original is now in the British

Museum.

One Anglo-catholic tradition that has not been lost here

is that the church should always be open, always be

welcoming. You enter through the small porch, perhaps not

fully prepared for the wonders that await. The nave you

step into is light, clean and well-cared for. There is no

coloured glass, no heavy benches, no tiles. The brick

floor and simple wooden chairs seem as one with the air,

a perfect foil for the rugged late Norman font, and the

rich view to the east, for the fixtures and fittings of

the 20th Century Anglo-Catholic tradition survive here in

all their splendour.

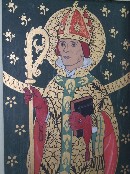

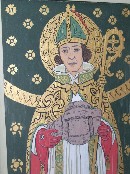

The two major features are the rood screen

and the high altar. The rood screen is the work of

several people, having been added to over the years by a

roll-call of prominent Anglo-Catholic artists. It was

designed by Ernest Geldart in the 1880s. It was painted

by Patrick Osborne in 1949, apart from the figures, which

are the work of Enid Chadwick in 1954. They are: St Felix

as a bishop holding a candle, St Thomas More in regalia,

St Thomas of Canterbury with a sword through his mitre,

St John Fisher as a bishop holding a book, St Alban in

armour and St Fursey holding Burgh Castle.

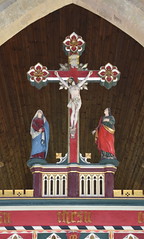

To one side, the Sacred Heart altar bears

the original stone mensa from the high altar. The table

itself is the Stuart Communion table. To the other, a

Lady altar. All of these are either gifts or rescued from

redundant Anglo-Catholic churches elsewhere. The elegant

grill in front of the rood loft stairs is by Ninian

Comper. Stepping through into the chancel is a reminder

of how the clearance of clutter can improve a liturgical

space. Here, the emptiness provides a perfect foil for

the massive altar piece. The altar itself was the gift of

Miss Eleanor Featonby Smith, consecrated by the Bishop of

Madagascar in 1956, in one of those ceremonies conducted

in the labyrinthine underworld of the Anglo-catholic

movement. The altar sports what is colloquially referred

to as the Big Six - the trademark six candlesticks of an

Anglo-catholic parish. Behind them, the rich reredos is

also by Ernest Geldart, and was also painted by Patrick

Osborne.

At the west end of the nave is a display case holding

facsimiles of the Kettlebaston alabasters, an oddly

prosaic moment. But Kettlebaston's medieval past is not

entirely rebooted, for the chancel was sensitively

restored by Ernest Geldart in 1902 with none of the

razzmatazz of his church at Little Braxted in Essex. The

east window was rebuilt to the same design as the

original, as was the roof. The late 13th Century piscina

and sedilia are preserved, and on the north side of the

chancel survives an impressive tomb recess of about the

same date. The sole monument is to Joan, Lady Jermyn, who

died in 1649. Her memorial is understated, and its

inscription, at the end of the English Civil War and the

start of the ill-fated Commonwealth, is a fascinating

example of the language of the time. Is it puritan in

sympathy, or Anglican? Or simply a bizarre fruit of the

ferment of ideas in that World Turned Upside Down? Within

this dormitory lyes interred ye corpps of Johan Lady

Jermy it begins, and continues whose arke after

a passage of 87 yeares long through this deluge of

teares... rested upon ye mount of joye. And then the

verse:

Sleepe sweetly, Saint. Since thou wert

gone

ther's not the least aspertion

to rake thine asshes: no defame

to veyle the lustre of thy name.

Like odorous tapers thy best sent

remains after extinguishment.

Stirr not these sacred asshes, let them rest

till union make both soule & body blest.

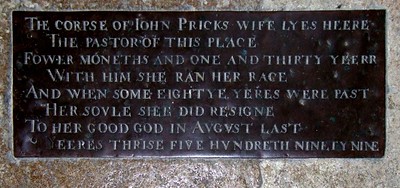

Not far off, and from half a century

earlier, a rather more cheerful brass inscription

remembers that:

The corpse of John Pricks wife lyes

heere

The pastor of this place

Fower moneths and one and thirty yeerr

With him she ran her race

And when some eightye yeres were past

Her soule shee did resigne

To her good god in August last

Yeeres thrice five hundredth ninety nine.

And yet, you notice, we never learn her

name. Above, the roofs drip with hanging paraffin lamps,

the walls have their candle brackets, for this little

church still has no electricity. You sense the attraction

of Benediction on a late winter afternoon.

St Mary is loved and cared for by those who

worship in it. There are rather more of them than in

Father Butler's final days, but they are still a tiny,

remote community. Since 1964, they have been part of a

wider benefice, and must toe the Anglican mainstream

line, as at Lound. But also, as at Lound, the relics of

the Anglo-Catholic heyday here are preserved lovingly,

and, judging by the visitors book, it is not just the

regular worshippers who love it, for Anglo-Catholics from

all over England still treat it as a goal of pilgrimage.

I remember sitting in this church on a bright spring

afternoon some twenty years ago. I'd been sitting for a

while in near-silence, which was suddenly broken by the

clunk of the door latch. Two elderly ladies came in. They

smiled, genuflected towards the east, and greeted me.

Together, they went to the Sacred Heart altar, put a

bunch of violets in a vase on it, and knelt before it.

The silence continued, now with a counterpoint of

birdsong from the churchyard through the open door. Then

they stood, made the sign of the cross, and went out

again. Father Butler looked on and smiled, I'm sure.

Simon

Knott, October 2018

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Churches of East

Anglia websites are

non-profit-making, in fact they

are run at a loss. But if you

enjoy using them and find them

useful, a small contribution

towards the costs of web space,

train fares and the like would be

most gratefully received. You can

donate via Paypal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|