| |

|

| |

|

This is a sparsely

populated part of Suffolk, the rolling landscape

with its fields and copses punctuated by the

occasional settlement. The medieval parish

churches are often remote, and Sotherton's is no

exception. There is a footpath to it marked from

the Halesworth road, but on the one occasion I

took it I ended up lost in a farmyard, and ended

up having to go the long way round. A narrow lane

rises up from the Beccles road, and it was with

some surprise in October 2018 that I cycled up

this to overtake a man struggling to push a

cement mixer. He stopped for a rest, and we said

hello. I asked him if he was alright, and he said

he was, or at least he would be when he got it to

the top of the rise. This was where the church

was, and the lane finishes just beyond it, but I

saw him carry on with his cargo, so I don't know

where he was going.

There is no village. Even the Parish of Sotherton

is too small to be marked on anything but a

decent Ordnance Survey map. The only other

buildings in sight are a cottage on the edge of

the churchyard, and an old farmhouse beyond. The

farmhouse's position in relation to St Andrew

gives it a proprietorial air, and you feel that

in times past the church might actually have been

an organic part of the farmyard complex, as at

Letheringham. The fields lift around to enfold

the little church, and when the corn is as high

as a cyclist's eye it gives an intensely

secretive feel to the place, as if something

buried deep in the past is hidden here. If you

come here while the harvest is in progress it can

feel as if the land is being stripped back to

reveal a profound secret.

This charming little church was completely

rebuilt by the Victorians. But they reused the

old materials, and at any rate this is a church

worth visiting. It is a fine example of good 19th

century rural work. The architect was Henry

Ringham, most familiar from his superb wood

carving in the Ipswich area, particularly at

Woolpit and Great Bealings. He built the fabulous

Gothic House in east Ipswich, but went bankrupt

before he was able to take up residence. However

he was still considered a significant enough

Ipswicher at the turn of the century to have a

road named after him.

I was disappointed to find the churchyard devoid

of sheep. On one memorable occasion I had arrived

here to find the church playing host to a flock

of the friendliest and most inquisitive sheep I

have ever encountered. They rubbed themselves

against me like sleek cats, and generally did all

that they could to get in my photographs. I spent

longer looking at the outside of the church than

I did the inside, and quite missed them when I

had to cycle off in the direction of Uggeshall.

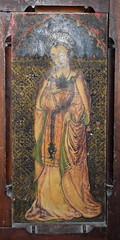

For such a quiet and unassuming church, without a

tower or a prominent position, St Andrew is full

of interest. It has at least one surprise, and

one great treasure. This is a pair of surviving

panels of the roodscreen. They are attached to

the vestry door. Although they have clearly been

overpainted, they retain their 15th century

gessowork (plaster of Paris attached to wood or

stone, and then painted). More remarkably, St

John is accompanied by his symbol of an eagle.

This is one of only two times this symbol is

known to survive on a roodscreen panel in East

Anglia.

There are other medieval survivals. The font is a

good example from the eve of the Reformation,

with a hint of the elegance which the English

Renaissance might have brought if we had not

chosen the Puritan path instead. The blockish

early 17th century font cover is a rustic

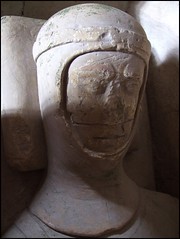

contrast.The surprising survival is the 13th

Century effigy of a knight, sleeping soundly in a

recess on the north wall. The matching recess on

the south side is empty, but is was probably

simply a Victorian affectation to have two of

them.

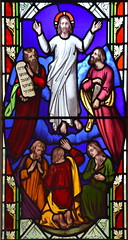

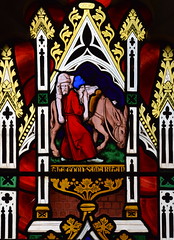

The 19th Century glass is singular. It is an

unusual collection. Although it must date from

the 1850s, some of it appears earlier, because of

its pre-ecclesiological style. Perhaps that is

simply because this is such a backwater. There

has been some confusion about the workshops

involved, but James Bettley revising Pevsner

teased out the details. The most striking window,

depicting the Ascension of Christ and the Day of

Pentecost, is by the Liverpool firm of Forrest

& Bromley. In a similar style on the other

side is the Transfiguration by Ward & Nixon.

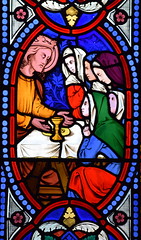

The Pentonville workshop of Charles Hudson was

responsible for the window depicting St Andrew

and the Good Samaritan, his also the Wise and

Foolish Virgins sequence.

Another period piece is the painted reredos, now

reset on the north nave wall. It depicts a sparse

crucifixion, and was made for the church by

Laurence Carrington Grubbe, and installed here in

1903.

On this beautiful sunny day in late October, the

church was full of light, the stone and wood

dusty, the plaster crumbling. A rough and ready

place to be sure, but with a sense of its past

and a feeling that it is still watched over by

its present custodians. An odd addition since my

last visit was a child's coffin in the chancel

with (I kid you not) a headless statue inside it.

I'm not sure what that is all about.

Munro Cautley was harsh about St Andrew, reviling

its 19th Century rebuilding, and of course it is

an insignificant church in comparison with the

remarkable treasure of nearby Westhall. But I

think this church is lovely. What's more, it is

still in use, welcoming to strangers, and a

delightful survival of the sentiments and

impulses of our recent ancestors, just out of

sight.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, November 2018

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Amazon commission helps cover the running

costs of this site

|

|

|