| |

|

| |

|

Until its clearance in the

post-war years, the area spreading

eastwards of Ipswich town centre was a

vast slum. The Rope Walk area was

redeveloped and is now home to Suffolk

New College and parts of the University.

The housing in the Cox Lane area became a

car park. I met a man a few years ago who

always tries to park his car on the site

of the house where he grew up.

Two grand red brick churches survive as

islands. The Anglican St Michael is now a

burnt out shell. It was declared

redundant in the 1990s, and in truth it

is hard to see how it can ever have been

needed as more than a triumphalist

gesture, with the parish church of St

Helen only a hundred yards or so away. It

was destroyed by fire in March 2011.

Still standing tall is George Goldie's

1861 Catholic church of St Pancras. Seen

from across the car park, the only clue

that it was once tightly surrounded by

poor people's houses is that there are no

windows in the wall of the north aisle.

As at Brighton's St Bartholomew, this

great ship was designed to sail above

roof tops.

St Pancras looks like a bit dropped off,

and that is exactly what it is. Goldie's

commission was for the huge, recently

demolished School of Jesus and Mary on

the campus of the Woodbridge Road church

of St Mary, and this town centre church

in the same style. St Pancras was

intended to be the start of a church of

cathedral scale, of which the surviving

church was but the chancel. At the time,

Ipswich was in the Diocese of

Northampton. Today, it is in the Diocese

of East Anglia, with a great stone Gothic

cathedral at Norwich. But the Norwich

cathedral, built as the church of St John

the Baptist, and the equally grand Our

Lady and the English Martyrs in

Cambridge, were both begun a good thirty

years after St Pancras. If it had ever

been finished, St Pancras would have been

one of the biggest red brick churches in

England.

The north elevation is stark, that on the

south side rather more comfy, with good

modern glass in the south aisle windows.

The most impressive view is from the

west, where the vast rose window fills in

what would have been the top of the

chancel arch. Here, where the 1970s

parish hall stands, would have been the

crossing tower, with transepts either

side. Looking further west, the nave

would have stretched, and here is perhaps

one of the reasons why St Pancras the

great was never built. Immediately to the

west of the church, across Cox lane,

stands the fortress-like Christ Church.

Although the present building post-dates

St Pancras, there has been a

Congregationalist church on the site for

more than three hundred years, and the

planned Catholic church would have

stretched in front of it. Given the

ecclesiastical politics of the late 19th

century, one can't imagine them giving up

the site very lightly.

The Catholic presence in Ipswich had been

re-established in the 1790s, at the time

of the French Revolution, by a refugee

Priest, Louis Simon. He said Mass in the

home of a rich local lady Margaret Wood,

and then with her help established a

mission church near the Woodbridge Road

barracks. This church, St Anthony, formed

the transepts of the building that still

survives as the parish hall of the 1960

St Mary.

After the re-establishment of the

Catholic hierarchy in England in 1850,

which you can read about on the entry for

St Mary, the plan was to create a town

centre profile for the Church, and this

was why Goldie was commissioned to build

St Pancras. However, anti-Catholic

feeling was rather stronger than it had

been seventy years previously. On a night

in November 1862, the protestant

ministers of the town whipped up such a

state of hysteria that angry mobs ran

through Ipswich smashing windows of

Catholic churches, homes and businesses.

Although the exterior of this building is

rather severe, the inside is a delight,

quite the loveliest Victorian interior in

Ipswich. It doesn't have the gravitas of

St Mary le Tower, or the mystery of St

Bartholomew, but it is a cascade of red

and white brick banding, cast-iron

pillars and wall tiling. Along with the

statues and the candles and the smell of

incense, it is everything a 19th century

town centre church should be.

The post-Vatican II re-ordering of the

sanctuary has not destroyed its coherence

(or, indeed, the traditionalist flavour

of the liturgy here). Above the altar,

Christ stands in majesty, flanked by the

four evangelists. The tabernacle is set

curiously off-centre to the south.

Exposed as St Pancras is in comparison

with many town centre churches, it is

always full of light, and this light

takes on the resonances of some good

glass. The west window was filled with a

design depicting the descent of the Holy

Spirit as recently as 2001, by the

Danielle Hopkinson studio. As a point of

interest, they also did the glass in my

front door. This is unfortunately

obscured by a massive organ (the west

window, not my front door). Below the

west gallery is the baptistery, one of

Ipswich's busiest, and just some of the

church's collection of devotional

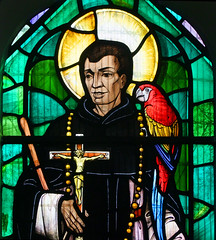

statues. In the south aisle are three

sets of triple lancets. The older glass

in the most easterly depicts St Thomas,

St Andrew and St John. The splendid 1974

glass by John Lawson in the other two

sets depicts St Martin de Porres and St

Francis of Assisi.

Not many people live in the parish

itself, but as the busiest town centre

church in Ipswich St Pancras continues to

have a major role to play. Its Masses

attract people from far and wide,

including many from the town's sizeable

minority communities. Perhaps this is

because it does have such a

traditionalist flavour, but also perhaps

because of the work of the tireless and

charismatic Parish Priest, Father 'Sam'

Leeder. 'He's been here for forty years,

and is a familiar character in the town

centre, wandering the streets and talking

to local traders, as well as being the

cornerstone of the town's scouts. Ipswich

would be diminished without him. |

|

Simon Knott, December 2018

|

|

|