| |

|

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

Wenhaston, pronounced wenn-er-st'n,

is a fine village on the Blyth, not far from two of

Suffolk's most important stopping off places for church

explorers, Blythburgh and Westhall. One of the thrills of

visiting Suffolk churches is the anticipation and shock

of amazing medieval survivals. There is that font at

Westhall, the retable at Thornham Parva, the wall

paintings at Wissington and North Cove, and much else

besides. Some churches, like Ufford, Bramfield and

Westhall, seem to have more than their fair share. It is

easy to blame the Victorians for destroying medieval

features, but, in many cases, it was the Victorians who

rescued and restored them. Many of the medieval objects

in our churches today would not have survived if it were

not for the Victorians. And yet, perhaps the most

significant medieval art object in the county exists by a

supreme irony, for if it had not been for an act of gross

19th Century carelessness, it might not have survived at

all.

If they had been efficient, the decaying wooden tympanum

taken down from above the chancel arch at Wenhaston in

the summer of 1892 would have been stripped, repaired and

painted. Instead, it lay out in the churchyard waiting

for someone to do something with it, while the

restoration continued inside. That night, it rained. The

whitewash, applied centuries before, dissolved. When the

workmen arrived on site the following day, they saw

wonderful things.

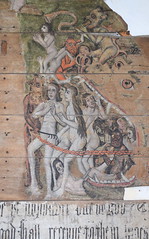

What the rain revealed is essentially a doom painting,

although there is a little more to it than that. A doom

shows the final judgement of souls after death; each

person comes equally before the throne of God, and is

selected to go to Heaven or to Hell. Probably, all

churches had them. The one at North Cove is on the north

chancel wall, but ordinarily the doom was above the

chancel arch, usually painted directly on to the plaster

as survives at Earl Stonham and Cowlinge. Where there was

no chancel arch, or the chancel was not sufficiently

lower than the nave to allow a painting, the top of the

arch would be infilled with a wooden tympanum.

Why is the Wenhaston Doom so significant? Although few

dooms survive in Suffolk, there are quite a few elsewhere

in the country. But the Wenhaston Doom is special for two

reasons. Firstly, in front of the chancel arch stood the

great rood, a feature of every medieval church, Christ

crucified, flanked by his mother and St John. The rood

was supported on a rood beam, or suspended from the

ceiling, above the roof loft and rood screen. Every

single rood in England was destroyed by Thomas Cromwell's

cronies in the 1540s. Not a single one survives.

We can see at Earl Stonham the way that the centre of the

doom painting has fewer details, since it would be

obscured by the rood. However, at Wenhaston, the rood

group was actually attached to the tympanum, and although

it was ripped off in the 1540s, the outlines of the

crucifix and flanking figures survive, like ghosts of

lost Catholic England. The other reason that the

Wenhaston Doom is significant is that its colours are so

bright, and its details so vivid. There's nothing else

like it in the country.

When was it built? Wills specialist Simon Cotton tells me

that in 1480 there was a bequest towards a new screen.

Since the tympanum would have followed the construction

of the screen and rood, then a date in the 1500-1520

period for the Doom seems likely. So it was completed

about 25 years before its destruction, that's all.

The last trump is sounded and the dead rise from their

graves. Christ sits on a rainbow, overseeing everything

that is going on. His mother and St John the Baptist

bring forward intercessionary prayers for the souls of

the dead. However, the real battle is between St Michael

and the Devil, who have charge of the scales, and weigh

each soul against its unreconciled sins. St Peter is seen

receiving nobility - we can tell from their headgear that

they include members of the Royal family, a Bishop and a

Cardinal. However, they are otherwise naked, to signify

that all are equal before God. So they'd better have a

good excuse... To the left, souls are received into

Heaven, while those on the right are marched off to Hell.

What happened to this amazing art object in

the middle of the 16th century? After the rood group was

removed and burnt, it was whitewashed over. Why was it

not removed? Simply, the order was that roods were to be

replaced with coats of arms, to remind congregations that

the State was in charge now. The tympanum provided the

best way of displaying the coat of arms as it had the

rood.

Fear God and Honour the King was the new

watch-phrase, but at Wenhaston, more was felt necessary.

Along the bottom of the tympanum (and thus below the coat

of arms) was added from St Paul's Letter to the Romans: Let

every soule submyt him selfe unto the authorytye of the

hygher powers for there is no power but of God. The

powers that be are ordeyned of God, but they that resest

or are agaynste the ordinaunce of God shall receyve to

them selves utter damnacion. For rulers are not fearefull

to them that do good but to them that do evyll for he is

the mynister of God.

When Edward VI died in 1553, and his half-sister Mary I

ascended the throne, the English Church restored its

connections with the European Church, and the coats of

arms were removed. Officially, the roods were meant to be

replaced, but this doesn't seem to have happened in many

places. Most likely, there simply wasn't time, for Mary

died in 1557, and the roods came tumbling down again

under the orders of her half-sister Elizabeth. The break

with Rome was made final, and the new Church of England

was born.

There seems to be an orthodoxy of thought that our

English churches were painted with pictures because the

people were ignorant, and this was their only way of

learning theology. There is no evidence for this. On the

contrary, the ordinary people of England seem to have had

a rich spiritual and liturgical life, to which the

furnishings of their churches only contributed a small

part.

No, the creation of these extraordinary folk art objects

was an act of devotion, and we mustn't get sidetracked

into thinking that they were lost because they were no

longer necessary. They were destroyed, wilfully and

purposefully. But some survived, and Wenhaston's Doom

painting is simply one of the most beautiful.

The chancel that once stood beyond it has gone, replaced

in the 19th Century with one that seems a little

over-grand for the size of the church. At the west end, a

charity board and a good royal arms for George III huddle

around the font. The font is instantly recognisable as

one of the Seven Sacraments series, but the reliefs are

all completely vandalised. The surviving colour reminds

one of Westhall, and this was probably in a group with

the similar fonts at nearby Blythburgh and Southwold.

You'll be appalled to learn that at least some of the

carvings survived into the early 19th century, until

someone took it upon himself to cleanse the font of them.

He's the one in the doom you can see being led away to

Hell.

Simon Knott, May 2019

Follow these journeys as they happen at Last Of England

Twitter.

|

|

|