| |

|

|

|

The parish of Wherstead

adjoins the borough of Ipswich on its

southern side, and Wherstead Road is

perhaps the grimmest of the main routes

into a town which does not always present

itself particularly elegantly to anyone

travelling into it. But Wherstead

churchyard is a remote, secretive place,

half a mile from the nearest road. It

used to be more remote: The track which

leads up to it has recently been blessed

with the pleasures of the Suffolk Food

Hall. In theory, it's a good idea -

expensive local produce is the very thing

to get the middle classes out of Tesco

and Sainsbury's. But I must say that I

baulk at shopping anywhere that describes

its stock as 'gourmet goodies'. Be

that as it may, you either linger or

scurry past the new neighbour, and carry

on up the track until you leave all the

noise and clamour behind you. At the top

of the hill sits St Mary in its

pleasingly rolling graveyard. From here

you have a view of one of East Anglia's

most famous landmarks, the Orwell Bridge,

which cuts the parish of Wherstead in

two. Behind you, hidden by rising ground,

is 19th century Wherstead Hall, once the

headquarters of Eastern Electricity, now

home to the privatised power company

currently calling itself E-on. Beyond

that, on the far side of the Manningtree

road, is television's "Jimmy's

Farm". But you would not know that

the modern world came anywhere near, to

stand here among the bird song and the

rustling of the bean fields.

|

Wherstead

has never been a big place. At the time of the

1851 census, when the population of many rural

East Anglian parishes reached their peak, there

were just 238 people living here. Despite the

proximity to Ipswich (the Cornhill in the centre

of town is barely two miles from this church) St

Mary is little-known. It is visible on its hill

top to a boat coming up the Orwell, which sprawls

dramatically in the valley below, but hidden from

the view of any road. The river leads the eye

south-eastwards to the cranes of Felixstowe and

Harwich. On the far bank, the brooding woods look

strangely foreign, as if we were in some kind of

outpost, and proper, wild Suffolk began over

there.

Until

the summer of 2008, I had never been inside this

church. Unusually for the Ipswich area, it is

kept locked, and I had never seen a keyholder

notice until a Sunday in June, when Martha and I

got out our bikes and went for a ride. Now, there

were three telephone numbers listed in the

lychgate. As I dialled one, it began to rain: but

it turned out that this was fortuitous, because

the churchwarden had been painting his garage,

and the rain meant he'd have to stop, and could

come over and open up.

St

Mary is pretty much an entirely Victorian church,

but one of particular interest. The architect was

Richard Phipson, who

restored the 15th Century tower and rebuilt the

nave and chancel, retaining the Norman south

doorway. Big lions along the roofline recall his

gargoyles at the town centre St Mary le Tower. Stepping

inside, the interior is almost entirely 19th

century, but of high quality, a testament to the

commitment and money of the Dashwood family of

Wherstead Hall. One possible medieval survival is

a composite figure of St Edmund in a window on

the north side, but it might be a Victorian

confection. The only later note is the lovely

1963 window depicting David the Shepherd and

David the King, by Dennis King.

While

Phipson's work is found at nearly a hundred East

Anglian churches, Wherstead's interior is raised

above the mundane by two of the great craftsmen

of 19th century Ipswich. Henry Ringham was a

woodcarver working in east Ipswich (Ringham Road

off of Cauldwell Hall Road is named after him)

and this was his last major commission. He is

responsible for the woodwork, including the

benches and the roof. Another Ipswich craftsman,

the stone mason James Williams, created the font

with its elaborate carvings, including a terrific

St Michael. There is more of his excellent work

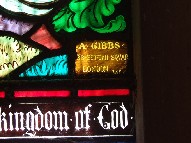

at Brome. The glass is also of the highest

quality, by important workshops: the Works of

Mercy in the west window are by William Holland,

while the two windows up in the sanctuary are

both signed by Alexander Gibbs. The pulpit,

carved by a Belgian workshop, is perhaps more of

an acquired taste.

| I had been worried by the

state of the church when we first

arrived: two windows were boarded up. It

turns out that this little church is a

regular prey to vandalism, and that is

why they keep it locked. Unfortunately,

of course, a culture of vandalism to a

building is a difficult thing to turn

around. Most East Anglian churches are

neither kept locked or vandalised.

Ecclesiastical Insurance asks parishes to

keep their churches open during the day,

because this dramatically reduces the

chances of vandalism. Most insurance

payouts are not for items stolen, but for

damage caused to doors and windows of

locked churches. It

is hard to suggest that Wherstead church

would benefit from being kept open when

it is already deeply enmeshed in a cycle

of damage, but you can't help thinking

that the fortress mentality of a handful

of Suffolk churches does them no good, as

well as little credit. Be that as it may,

this lovely little church deserves as

many visitors as it can get - why not a

welcoming sign down by the Suffolk Food

Hall, another up at Jimmy's Farm, and an

occasional open door for pilgrims and

strangers? It's worth a try.

|

|

|

|

|

|