| |

|

|

|

I hadn't been back to

Yoxford for years. If you are a cyclist, it isn't

the easiest place to get to. There are few

Suffolk villages which are only approached by

main roads, but Yoxford is one of them, and it

wasn't until August 2017, more than fifteen years

after my previous visit, that I took my life in

my hands and cycled down the A12 from Darsham.

And yet, I'd always liked Yoxford. I remembered

writing on the occasion of my previous visit that

if, against all my better judgements, a day came

when I tired of my shameless hedonistic urban

lifestyle and decided to retire to the country,

and money were no object, then Yoxford would be

pretty near the top of my list. It was big enough

to have three decent pubs, a few good shops, one

of which was one of Suffolk's best second-hand

book shops, and even had a railway station half a

mile to the north. And after all, the A12 didn't

actually run up the high street. There were some

pretty houses and even a park. And it was still a

village. What more could I want?

The name of the village means a ford where oxen

can pass (as, of course, does the name of the

city without the Y in front). The little stream

that comes down from the industrial village of

Peasenhall a couple of miles off is referred to

locally as the River Yox, but this is a

backnaming, the stream named after the village

rather than the other way around. Yoxford

proclaims itself 'the garden of Suffolk' as a

result of the intensive fruit farming that began

here a couple of centuries ago. And it will come

as no surprise to learn that Yoxford is

alphabetically last of Suffolk's 500-odd

parishes.

|

Well, the second-hand bookshop has

long gone, and so has one of the pubs. I couldn't tell

you if either of the others are still decent, as I didn't

call at them. But St Peter is still a fine sight with its

grand spire, so unusual in Suffolk. Obviously, given the

dedication, there is a cock on top of it. This church is

one of the last of what I think of as the large southern

Suffolk churches you meet heading north, before hitting

the Blythburgh/Southwold/Covehithe group which give a new

meaning to grandeur. And yet, stepping inside, it is hard

to shake off the impression that this is a town church,

for it has an urban quality to it. Partly, this is

because of the 19th Century restoration at the hands of

Richard Phipson, but it is also because of the monuments

and brasses that line the walls. Significant names from

Suffolk history can be found on them, for important

people seem often to have lived around here.

One of them not buried here was Charles Brandon, Duke of

Suffolk, who was the second husband of Henry VIII's

little sister Mary, who had previously been married to

the King of France. Their grand-daughter was Lady Jane

Grey, who for a brief, teenage week in 1553 was

proclaimed Queen of England by the desperate protestant

advisers to Edward VI, aghast at having a dead young king

on their hands. Their cunning plot to impose extreme

protestantism on England was foiled by the popular

acclamation of the accession of Mary I, who was staying a

few short miles away from here at Framlingham. Mary's

reign would prove to be short and unhappy, and young Jane

paid with her life for the treasonable actions of those

scheming old men. But if the protestants had succeeded in

their plan, England would have been quite different

today. There certainly would not have been a Church of

England, for instance.

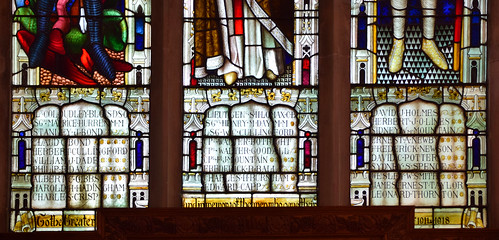

The view to the east is of wide

open spaces, with aisles running down to meet the

chancel. The focus is the War memorial east window of

1920 by Lavers & Westlake, depicting Christ in

Majesty flanked by St George of England and St Edmund of

East Anglia. What makes it so interesting is that the

names of the Parish dead are also in glass in the lower

part of the window.

It was almost half a millennium

before, at the end of another great war, that Thomasina

Tendrynge died in 1485, the year of the Battle of

Bosworth Field and in which the accession of Henry Tudor

would kickstart the dramatic events of the next two

centuries for the English people. Thomasina was the

daughter of William Sydney, himself an ancestor of the

family who would find favour with Henry's grand-daughter

Elizabeth a century later, being given Penshurst castle

in Kent.

Her brass, and those of her seven children, are set on

the south side of the sanctuary. Thomasina is wrapped in

a shroud, a striking if not unusual style for brasses at

the time. Two things make this one rather uncommon,

however. Firstly, she is stunningly beautiful, and she

gazes out at us with wide eyes from the elegant curve of

her winding. When he first saw her, my young son said

that she looked like a mermaid, and so she does.

Secondly, although two of her daughters stand beside her

in Tudor robes, her five other children are also in

shrouds, indicating that they died before she did.

A fine pair of earlier brasses nearby are to John and

Matilda Norwiche. We know very little about them, except

that they are responsible for St Peter's being here. John

was probably a member of the Norwiche family of

Mettingham castle. Matilda died childless in 1417. John

succeeded to the Lordship of Cockfield Manor in Yoxford

in 1422. He never took up the reins however, preferring

to remain elsewhere, possibly Mettingham. The Manor was

sold, and the proceeds were used to completely rebuild

this church in the prevailing Perpendicular style. John

himself died in 1428, and these brasses remain as a sign

on their patronage.

Two hundred years later, the Manor was in the hands of

the Brooke family, and Joan Brooke survives in the form

of a characterful brass in the south aisle. There are

several others, all worth a look. But these brasses

really should not be mounted on the walls. I realise that

this is done with the best of intentions, to allow them

to be displayed, and to protect them from being walked

on. The trouble is, if there was a fire, and these do

happen in churches from time to time, the brasses would

melt, and run down the walls. Floor-mounted brasses set

in stone do not melt, because the heat rises away from

them.

Later, the Manor would come to the Blois family, who were

remembered in the name of the pub that closed. St Peter

still remembers them, with a splendid array of ten

hatchments, mostly beneath the tower. There are also a

couple of fine wall monuments to the family, one of them

to the long-lived Sir Charles Blois, which has been very

clumsily relettered at some point. Mortlock tells us that

the sculptor was Thomas Thurlow, whose work can be found

widely in this part of Suffolk. Sir Charles was ever

feelingly alive to the duties of his station,

apparently, as well as being faithful and earnest in

the discharge of them.

My favourite memorial is a very simple one, but it

remembers one of the great and often unsung heroes of

church explorers. This is David Elisha Davy. The

agricultural depression of the 1820s pushed him into an

early retirement, which he spent travelling around

Suffolk, sketching and taking an inventory of the

exterior and contents of medieval churches.

It is no exaggeration to

say that he rediscovered Suffolk's churches,

which had mostly been in a state of neglect since

the early 17th century. His vast body of research

is still largely unpublished, although it is

possible to view it in the British Library, and

his lively account of his journey is available in

a Suffolk Records Society publication. This is an

absolute must-read for anyone interested in

Suffolk's churches - Suffolk Library Service has

loads of copies. Davy created a priceless record

of the county's churches on the eve of their

Victorian restoration. In many cases, his record

is the only one we have of the churches between

the Reformation and the modern age.

White's Directory of Suffolk tells us that, by

1844, Davy had already headed off to his other

house in Ufford. But Yoxford could still boast no

less than five tailors, four milliners, and even

a staymaker. The Directory also reveals that this

large village (1500 people even then) could

sustain a lifestyle considered so harmonious that

Anglican ministers of surrounding villages

thought it worthwhile abandoning their parishes

and living here instead. The Vicar of Ubbeston

for example (although that church is now a

private house), but also the Rector of Middleton,

Fordley, Westleton and Peasenhall, the splendidly

named Reverend Harrison Packard. Today, all these

villages come within the benefice of Yoxford.

Ironically, of course, those 19th Century

clergymen moved to Yoxford because of the

trappings of an urban lifestyle it could provide. |

|

|

|

|

|